Running money in the markets, particularly rising markets, there is always a sliver of ice in the back of your mind.

‘When will there be another panic event? Another crash?’

Markets are resilient. They can calmly price the trends they see. Until a black-swan event comes along.

Black swans were presumed not to exist until explorers discovered them in Australia in 1697.

Today, the expression defines high-impact but hard-to-predict inevitabilities.

Source: Image generated by AI (Canva)

The 2007 Global Financial Crisis was one such event. Liquidity seized up, and the S&P 500 dropped 57%.

The 2020 Covid-19 crash was another, where it dropped 34%.

In both cases, almost no one saw the crash coming. The black swan was unknown. Until it landed.

Could a canny investor have spotted a black feather on the path some months before? Were there early causes that led to these effects?

The other day, I was talking to the owner of a security company. His business looks after a large number of supermarkets across Auckland.

‘You can predict when trouble is going to spike,’ he tells me. He’s referring to shrinkage — shoplifting. ‘When there’s trouble in the Middle East and the petrol price jumps.’

Makes sense. Petrol goes up. People struggle. Supermarkets see a spike in thefts.

Black swans for this market?

We’re in a recovering market…

First, there was a global pandemic, where prices dropped about 35%.

The prices cratered because governments locked down businesses. Investors panicked. How can companies trade when they’re locked down?

But stocks quickly recovered because governments hosed markets with cash.

Then we realised much of that cash had come from cranking the money-printing machines.

There was an inflationary crisis. To battle that, the screws came on interest rates.

Markets are now showing recovery because that battle against inflation is nearing — though has not yet reached — a victory.

Meanwhile, there’s war in Ukraine and the Middle East. Though wars don’t tend to overturn markets too much unless they specifically disrupt businesses.

The war puzzle

Despite the initial jolt of uncertainty, war has historically fuelled markets.

Ben Carlson of Ritholtz Wealth Management reports:

From the start of World War II in 1939 until it ended in late 1945, the Dow was up a total of 50%, more than 7% per year.

Was this an isolated trend? A one-off event?

Well, no. We have seen the market behave like this in recent times as well.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the S&P 500 fell 7% in the weeks following the incursion. But a month later, the market rebounded, and the S&P was trading at a level higher than before the invasion.

Some stocks — for example, Rolls Royce [LON:RR] — benefited from defence spending. That company is up over 180% in the past year.

Uncertainty and disruption

Markets are most concerned by these factors.

They do not like uncertainty and tend to sell off at the outbreak of any panic event. Investors go to safe haven assets like gold, or seek out the most defensive positions.

Defensiveness will depend on the nature of the uncertainty.

During the GFC, McDonald’s [NYSE:MCD] held its value. When the pandemic hit, the stock plunged 32%. Investors fretted restaurants would have to close for months.

Once the market has digested the uncertainty, it then focuses on the driving force. Earnings. How much and for how long will earnings be disrupted?

This is what we missed following the outbreak of Covid-19. I underestimated how much governments would subsidise business earnings. While we did pick up many bargains and add large profits — these could have been even greater if we’d predicted government overreaction.

Coming disruption

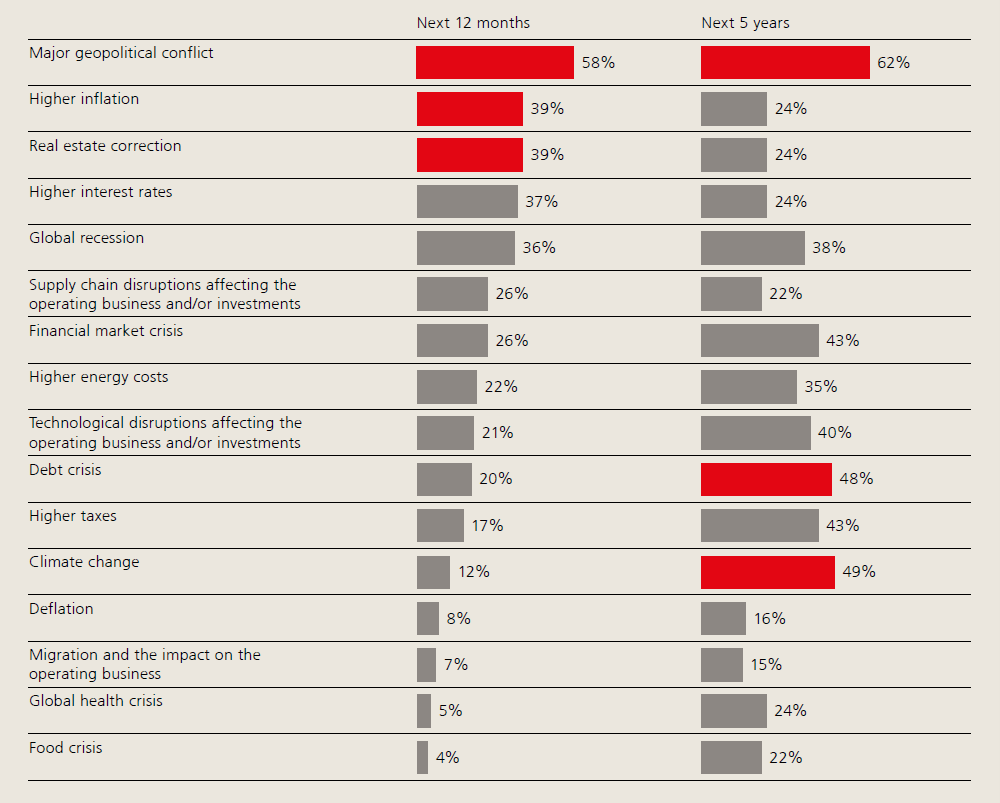

UBS’s recently published Global Family Office Report 2024 gives its survey of expected risks and disruptions:

Most of these are so anticipated, I reference them for one reason. To suggest to you which risks are probably already priced.

While geopolitics is the most difficult area to predict, localised conflict has yet to upset markets over a longer period.

A fight over Taiwan could be a different matter. Yet this risk has been flagged in Western investment reports since 1979.

The real upset to markets over the next 5 years may come from internal division.

Social and political divides

The credit-based economy has seen asset values (stocks and property) rise much faster than wages.

In the developed economies where we invest, there appear growing divisions in political outlook. The wedge between left and right seems more extreme.

Example: here in New Zealand, many who have missed out on the asset boom now sit alongside a growing left elite in a voting bloc that easily comprises 45%.

This saw support for a wealth tax to resolve inequality. The same scenario is seen in some US blue states.

What is missed is the effect of a wealth tax on capital markets.

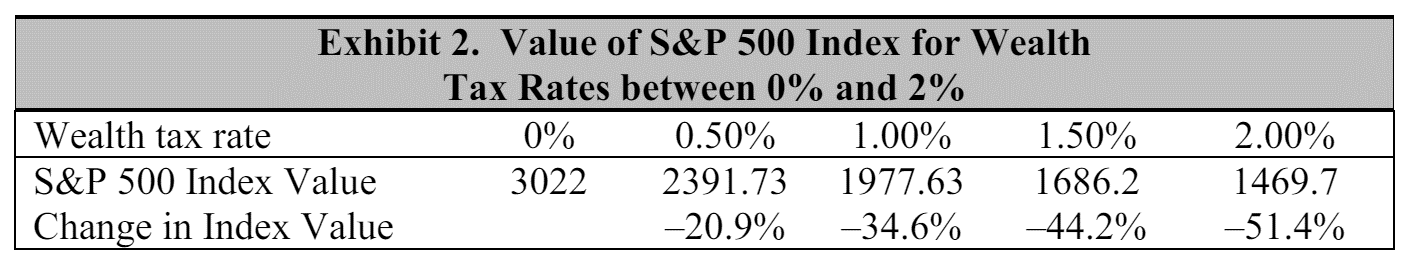

John Stowe, Finance Professor at Ohio University, has written a detailed paper, Wealth Taxes and Capital Markets (February 2020). He considers how a wealth tax pushes up the cost of capital, making many projects no longer economically viable.

In fact, investment ends up falling every year. Meaning there is less wealth to tax in the future.

This means less investment, less business, and fewer jobs. You likely end up with many more people falling below the poverty line.

As for the impact on the stock market, take a look at his modelling:

Yes, a 2% wealth tax could see the market fall over 51%.

Here in New Zealand, the Green Party were proposing a wealth tax of 2.5%.

Unlike in the US, the bulk of New Zealanders’ wealth is not in stocks but in property. We see no reason why this market will not react similarly to the S&P 500 index (above). Values crater so deeply the market would also face a devastating debt crisis.

Diversification

It’s the one free lunch in finance.

One way to avoid the disruption in one market is to be invested in another. While the pandemic was a global event, the risks of political and social division do not fall equally.

In Europe and Argentina, for example, the pendulum is swinging resoundingly in the opposite direction. Almost 70% of young Argentines voted last year for Javier Milei’s plans to slash government and taxes. Right-wing victories in Europe also follow anecdotal reports of younger voters fed up with high taxes and endless government deductions.

Here in New Zealand, a coalition has been given the chance to right the economy and improve home affordability. They have until 2026 to build confidence and secure their support.

Are you looking for someone to stand up for you?

Here at Wealth Morning, we run a night-trading desk focused on Europe and other global markets. We aim to build up defensive and profitable portfolios for our Eligible and Wholesale Clients.

When the next black-swan event does come, we’re ready to protect wealth. And to take advantage of the opportunity to grow wealth.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is the author’s personal opinion and commentary only. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. Past performance does not indicate the future. Wealth Morning offers Managed Account Services for Wholesale or Eligible investors as defined in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.