and how the rich are using this strategy to protect their wealth.

It’s a weekly breakfast routine. Now the price has doubled in just five years.

Come Monday, I take up the deal for a Bacon & Egg McMuffin and medium cappuccino. Absorb a couple dozen financial news sources and charts. Speak with or message a colleague. Then consider where the markets may head while draining the last of the coffee.

Disclaimer: I am a McDonald’s shareholder.

Source: Pixabay

Five years ago, working offshore, that McMuffin deal cost me £2 ($4.20).

Yesterday (on the app): $8.50!

I’m not lovin’ it as much now. Whose pay packet moves ahead at 20% a year?

But there’s one way you could’ve kept pace. And the wealthy have known about this since hyperinflation threatened the world.

Inflation: Stoking a fire

Well, there was no McDonald’s for much of 2020.

Here in Auckland, the business was in lockdown. Unable to trade, with the drive-through opened only later under limited conditions.

I manage wholesale portfolios in the global markets. In 2020, I was going through line by line, trying to work out how each position could ride out the storm.

We took some risk to buy into startling bargains that emerged. As it turns out, we didn’t buy enough. Because we underestimated something: governments and central banks flooded economies with fiscal and monetary stimulus. Companies were paid to close their doors. Interest rates fell to record lows.

Apparently, there were lessons from the GFC. Politicians and bankers had acted too little too late then.

This time, they reacted indiscriminately. Turning on a fire hose of cash. And locking down not only once, not only those vulnerable, but many times for everyone.

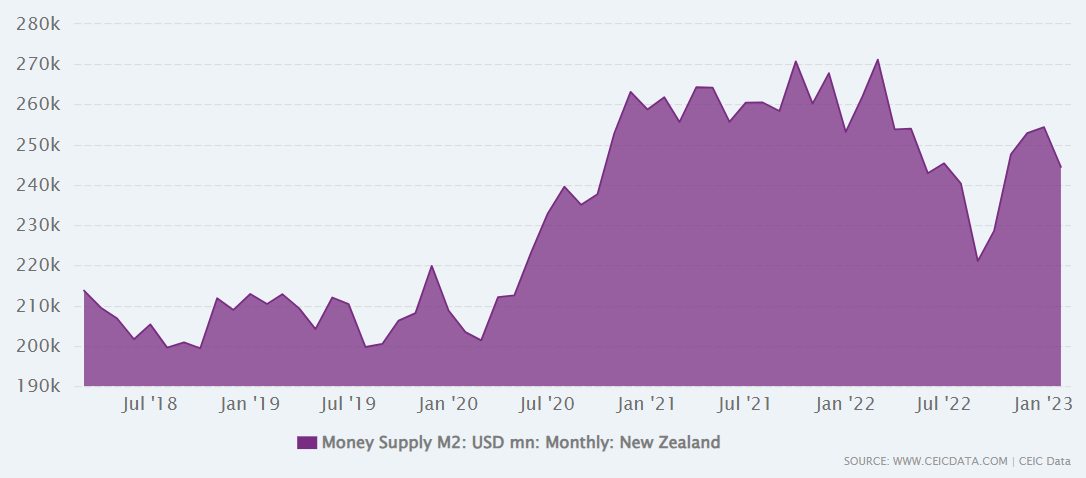

What was the financial impact from subsidising lockdowns? A near 35% increase in the money supply in New Zealand:

Coupled with supply disruptions, no wonder we’ve faced too much money chasing too few goods.

In 2021, this started to skew markets. Artificially low interest rates stoked a housing market frenzy.

Today, in 2023, we’re under the bitter medicine of ‘higher for longer’ interest rates. And the time horizon for them to come down is becoming too long to predict in a volatile world.

But they’ll come down at some point as the developed world ages and growth suffocates. That creates opportunity right now.

Inflation: A threat to democracy?

A cost-of-living crisis has fuelled some of the worst levels of division and inequality this country has seen.

Depending on how you see the world, we can try to fix this by either growing the pie, or slicing it up more.

Trying to tax your way to a more prosperous economy is laughable. As Churchill put it, ‘Like a man standing in a bucket and trying to lift himself up by the handle’.

Yet intense inequality can incite revolution and risk democracy.

For the first time I can remember, we saw property rights — a cornerstone of democracy —under threat this election campaign.

The Green Party campaigned for a wealth tax, targeting the assets of productive people. It was indiscriminate. Own a business or farm worth more than $5 million, employing people? You’ll be penalised. Likely forced to sell and break that up for the benefit of the proletariat.

Before the emergence of alternative media outlets, it’s been hard to find a strong differing point of view to the left-leaning narrative. Trust has been undermined by government sponsorship of the media. Calling into question their independence.

AUT’s Centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy found falling rates of trust in mainstream news media. This year, that fell to 42%.

Amongst our high net-worth client base, I sense their mainstream media trust level to be nearer zero.

Will the new government stop funding bias and promote economic freedom? I sure hope so.

At the extremes, there are lessons from history

In the 1920s, Germany’s Weimer Republic saw hyperinflation.

This impoverished and divided millions. And it paved the way for the next government to take power as democracy crumbled and media propaganda took hold.

Political cartoon of the time. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Yes, governments tend to ‘print money’ to resolve crises. Then deal with the aftereffects later. Often, it’s too late and the damage has already been done.

In Germany’s case, inflation ran out of control. So too did crime. Ships were looted as they came into harbour. Gangs of armed men stormed countryside barns for food. And shops restricted their hours and covered their windows with iron grills. Perhaps there were ram-raids?

The Weimar Republic’s crisis dragged much of the middle class into the working class. Those on fixed incomes suffered most as prices spiralled out of control. There was a housing crisis.

One interesting phenomenon was how the wealthy managed to protect, even grow their wealth, through this time.

Stocks proved the best way to preserve purchasing power over a period of years. These businesses still had real assets, sales, and profits. Even in the devastated Germany of the 1920s.

The lesson remains: the best shot you have to grow your wealth is to own some quality assets. That’s the best long-term protection against calamity. Even through World War II, stocks proved a reasonable bet in the long run.

Building and protecting prosperity

Inflation benefits the wealthy because they own real assets. Further, they can more easily access borrowing to buy discounted assets during times of crisis.

This also fans division and heightens risks of more state control.

A country’s best bet is to stamp out inflation with a single focus from the central bank. Then work to restore opportunity, particularly to working people across the economy.

Unfortunately, in New Zealand, this situation is compounded by a housing crisis. Home ownership is concentrated amongst families with generational capital.

This concentration likely increased when home prices reached record levels in November 2021. Prices have still not returned to pre-pandemic levels across much of the country.

Since so much of this country’s wealth is tied up in housing, there’s a clear wealth effect. This influences all other capital investment. It becomes political suicide to allow home prices to fall too much.

Our housing market is a pond that must be kept at a certain watermark to keep the boats afloat.

Even the previous government seemed more than willing to open the immigration floodgates. Especially when it became clear that the economy could slip into a deep recession if house prices were left to fall.

Of course, immigration is also one of our best shots at growing the economy. Providing the skill base coming in generally exceeds that already within the country.

If we want to catch up Australia, we need to grow GDP faster. That needs investment and skills.

Ideally, we’ll need to build our way out of this crisis, such that house prices are no longer sources of speculative growth. And capital can focus on productive investment into business.

Yet history tends to show that this often happens only after a crisis. World War II left German housing devastated with 20% of the supply in rubble. The government had to spur building at scale and keep prices stable.

There are similarities with Christchurch here. The earthquake meant building had to be expedited. Now homes there are among the most affordable for a main centre. Though that is changing.

Today Germans are more likely to be debt-shy and rent their homes rather than own them. They’re also more likely to invest in businesses and stocks.

There are lessons in crises and from the past few years.

Cash is a deceptive king. But quality assets, with returns compounded, can build and preserve your wealth.

The millionaire path

If you’re starting out, the first million is the hardest. You’ll need to offer some value. Take pride and pleasure in your work. Buy growth assets you can afford. And you’ll reach it.

The second million is also hard, because you have to double the first (a return of 100%).

The third million, not so much, as you simply need to return 50%. That’s possible with compounding over a few years.

The fourth million gets easier, a return of 33%. The fifth, 25%. And for the sixth million, you only need to return 20%. Which, when the market is ripe, some investors have managed to return inside a year.

The key is to find stocks, property or other quality assets you can access that outpace inflation. Then you’ll keep well ahead of those McMuffin price jumps.

At Wealth Morning, we run what may be the only active night-trading desk in New Zealand for our Eligible and Wholesale Clients:

- Every week, we aim to buy into exceptional companies in the UK, Europe, Australia, the USA, and beyond.

- Our focus is on sectors that offer the perfect balance of growth and income.

- We are interested in businesses that offer great return on equity, margin of safety, and the ability to grow earnings over time.

- Our mission? To capture pockets of outstanding opportunity where we can compound wealth.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

This article is the author’s personal opinion and commentary. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. Wealth Morning Managed Accounts are only available to Eligible Investors and Wholesale Investors (not to Retail Investors) as defined in the Financial Markets Conduct Act (2013).

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.