Amidst the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020, a friend decided to go swimming.

As she advanced into the water, she was suddenly startled by screams from the shore.

Somebody was yelling at her to get out of the water!

Her immediate thought was that a shark had been spotted in the harbour.

As she made her way out of the water, back on to the sand, the ‘Karen’ that had been shouting fled further back. And said that she was ‘breaking the rules.’

Source: My Guide Auckland

Now, this was Cheltenham Beach, Devonport. One of the calmest swimming beaches anywhere. The chance of anyone getting into difficulty and needing help — or meeting a shark — are very rare indeed.

It seems crazy to reflect on this now. But we need to acknowledge this was a time of peak fear. The virus was new. And while an initial lockdown was warranted to get things in order, few lone voices were calling out the overreaction that followed.

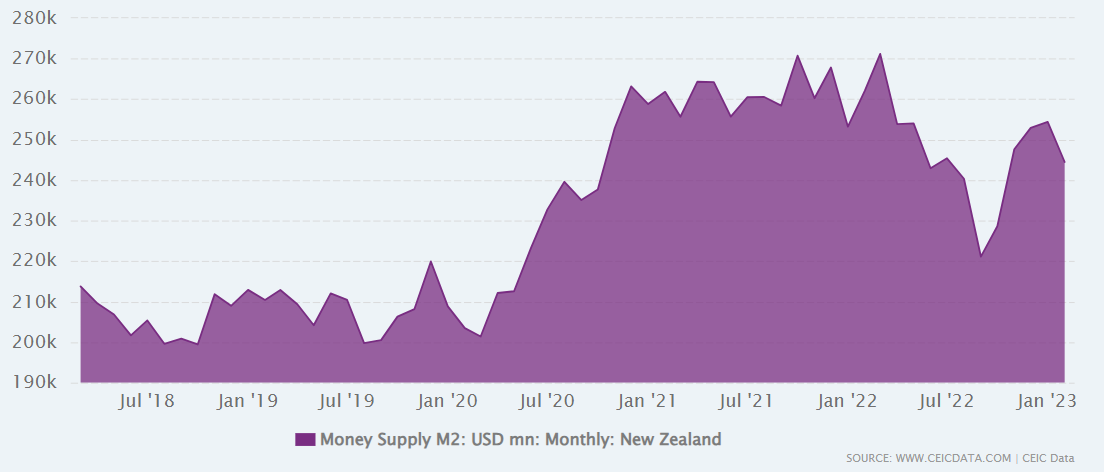

Since the pandemic, the dramatic increase in M2 money supply (around 35% here in New Zealand) has caused market volatility on the back of inflation.

The overwhelming feeling I’m getting is this: as during the pandemic, fear is latent and often manifesting in the wrong areas. This can lead to poor decisions.

Let’s take a look at some of the current economic challenges that are putting the fear in Kiwi investors. And we’ll try to separate the real risks from overwrought fear.

1) China’s slowdown

China is grappling with deflation, high levels of corporate debt, and liquidity risks in its giant property sector.

Deflation is made worse by a growing determination amongst key trading partners like the US to move the subcontracting of manufacturing elsewhere. Chinese factories faced with unsold goods try to offload them on the local market at cut prices.

The immediate risk that springs to mind is around New Zealand’s export business. Our trade deficit reached worrying levels last year. We can ill-afford demand drying up in our largest export market.

But this is probably the lesser concern. With a population of 1.4 billion people, we only sell to a very small segment of that. Despite the economic troubles, new households are still joining the middle and upper classes every week. Thus becoming potential target customers for the Kiwi food bonanza.

The real fallout from China’s slowdown is the damage to the New Zealand dollar.

As I write today, NZD is well below 60c USD. It is weak against all the other majors. Even AUD, which itself is weaker on China concerns.

This makes it harder for Kiwi investors to diversify their investing globally. And it makes it more expensive to import consumer goods and key inputs in production, like fuel and fertiliser.

Unfortunately, this feeds into the more pernicious and real damage caused by inflation.

2) High inflation, higher interest rates

Despite one of the higher central bank rates in the developed world (OCR at 5.5%), inflation is still running hot here in NZ at 6%.

The US, with the same Fed rate at 5.5%, has seen inflation fall to around 3%.

This is a most prominent pricing force in equity markets.

When investors can get 6% on fixed interest, they’re less inclined to venture into the riskier area of equities.

And they’re rightly concerned about the impact higher interest rates will have on leveraged businesses. Particular in the property sector, where valuations are falling.

Further, as higher interest rates weigh on the economy, there is the very real threat of continued recessionary slowdown.

We are seeing this on the retail streets of New Zealand. Many households are struggling with mortgages and the cost of living.

But thus far, the US seems to have avoided a recession. Strong demand coupled with growth in key areas — like household formation, clean energy, artificial intelligence, and the military — are helping to maintain buoyancy.

Any global slowdown may reflect a reconfiguration of growth away from China, to other productive parts of the world, such as the US, Mexico, India, and South East Asia.

The clear and present risk for New Zealand is this. A failure to get inflation under control (within the target of 0-3%) will see continued economic volatility and a deeper recession as higher interest rates bite.

3) Ukraine: War in Europe

I heard someone the other day saying that Russia was making more money than ever by selling oil to China. And that the economy is doing better than expected despite the sanctions.

Their implication is that the West’s support for Ukraine might be misguided.

I find this heartless and probably ignorant.

There is only one alternative to not supporting Ukraine. And that is to green light for Ukraine — an independent country since 1991 — to be invaded and absorbed into Russia.

If you believe that position is acceptable, then what if Malaysia desired to absorb Singapore again? Or for any other larger country to take over a smaller neighbour?

In fact, the numbers show that Russia is being further crippled by this misadventure. The 27% decline in the ruble and the flight of capital from the country suggest the lot of most Russians has been substantively diminished. Just this week, Russia’s central bank lifted rates to 12%.

For investors in global markets, the wider risks from Ukraine is less than what many may fear.

Russia and Ukraine are bit players when it comes to global GDP. And threats to European energy have largely seen countries find alternative sources.

Although Russia cut 80% of its historic natural gas deliveries to Europe in 2022, Putin’s energy gambit against Europe has failed. The crisis accelerated the construction of new import terminals for LNG. And rapid growth in renewable installations.

Further, many EU states had actually been planning energy security investment for some years. They were readier for transition than Russia expected.

Whatever your view on Russia and Ukraine, most evidence points toward a weakened Russia and a more energy-resilient Europe.

It is a timely reminder that, in economics and investing, there is often some free lunch available via global diversification.

Also, it’s a timely reminder that virtually no one is as indispensable as they may think.

And that brings us to the greater risk…

4) Taiwan: War in Asia?

Taiwan currently scores 94/100 for freedom. Can it stay this way? Source: Freedom House

It was recently reported that prominent China hawk Kyle Bass said that Beijing could attack Taiwan by 2024, ‘bringing war to the West’.

The founder and CIO of Hayman Capital Management says that Xi, like Putin, is more concerned with territory than economic fallout.

He believes Wall Street is miscalculating how much weight the Chinese leadership places on the economic risks.

‘We on Wall Street love to think he would never do that because it doesn’t make economic sense. We have to stop thinking that way and literally start listening to what the man says.’

Perhaps Mr Bass has some short positions on China or Taiwan and some long ones on military stocks?

You can speculate on China all you like. But military intervention still seems unlikely.

While I agree with Bass that the considerations may be beyond economic, the trajectory of China has focused on peaceful resolution, not war.

Why would you seek a peace plan with Ukraine, attempt to position yourself as a global peacemaker, and continue to engage diplomatically (though at times aggressively) with Taiwan if you wanted war? You’d risk destroying any diplomatic gains made.

Still, the threat to Taiwan’s self governance raises ongoing geopolitical risk.

As Europe has done with energy, it would be prudent for investors and the West to use this juncture. To build resilience in key areas like semiconductors and essential manufacturing.

For New Zealand and Australia, any disruption in the South China Sea will hit our export economy more than most. And we too should look to diversification.

5) US political upheaval

Listen to opponents of the US, and you could be led to believe that the world’s largest economy is on the brink of civil war.

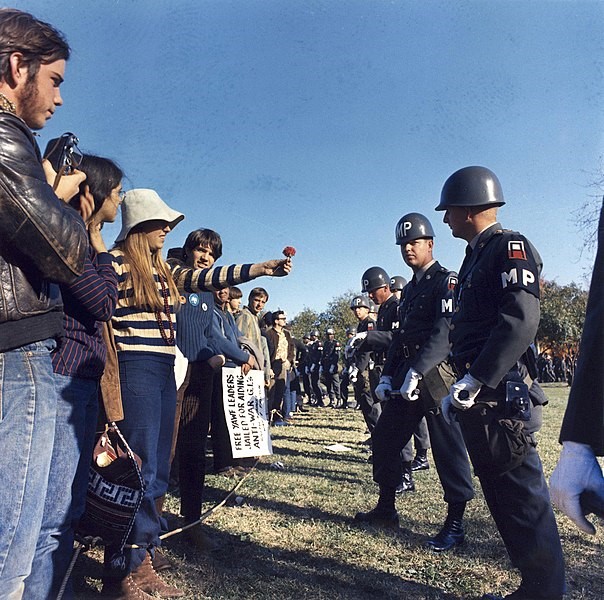

In fact, political dissension appears less than during the Vietnam War.

Anti-Vietnam War protests. Source: Wikimedia Commons

While the January 6, 2020 insurrection seemed shocking, the actual level of violence was relatively low. And the Constitution was ultimately upheld.

The reality for most Americans is this: while politics can be polarising, American society is still more socially cohesive than in many other large countries.

Further, there is a common, unified, and multicultural optimism in simply ‘being American’.

This is not to say there won’t be protests or tensions in the upcoming Presidential election. And the media will persist with its ‘orange man bad’ attacks, to the ire of MAGA Republicans.

But when it comes to the real roots of civil war — ideology, racism, social class, and actual policy — the gulf between Republicans and Democrats is hardly extreme. The wounded pride of Trump and his supporters is real. But not something anyone will go to war over.

What we will hopefully see is the wisdom of opposing crowds repositioning a finer pendulum in American politics. And a wise new leader emerge who can recalibrate the American Dream.

At the core of all these fears is a lack of empowerment

News is available in your pocket on a mobile device 24/7. But very little of what happens has immediate or lasting impact. It is best to digest, but seldom react.

Then there are economists weighing in with new warnings. By the time they analyse the trend, it has likely already moved.

Why would you work as an economist at a bank if you truly knew where the economy was heading? You’d be deploying money in the markets and positioning yourself for a killing.

As Warren Buffett remarked, ‘In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.’

Yes, in the short-term, the market can be subject to irrationality and fear of nonexistent sharks or other unseen risks. But in the long-term, the market looks beyond sides. It looks beyond prejudice and bias. And it focuses on price signals.

On that note, the main price signal we see is inflation slowly coming under control in the developed markets where we invest. This is occurring as key labour and housing markets hold up pretty well.

That could present a lot of upside for those with a patient and global view.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is the editorial content of this periodical. It is the author’s personal opinion and commentary. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.