The road in front of our office was taken over by the police last month.

You could see 40 or so police vehicles lined up along Quay Street, Central Auckland.

I had to negotiate with a policewoman holding an assault rifle to duck under the tape to enter our building.

Meetings were cancelled. Nobody could drive into this part of town. The ferries were turned back.

From the 26th floor. Source: Author

The police response to a shooter who murdered two of his former workmates was strong. They responded with speed and firepower.

Having spent some years driving into French cities — tourist centres on public holidays — the sight of well-armed police is nothing new.

But there, it follows the risk of terrorism.

The shooting in New Zealand and wave of violent crime we’ve seen since the pandemic seems to stem from a sector of society in chaos.

Lack of police resource does not appear to be the main problem.

As with most social factors, the roots lie in economics.

When people don’t feel they can keep pace with the cost of living and they struggle to afford a reasonable and safe home, fractures can break.

There are plenty of fractures already evident. Family breakdown. Welfare dependency. The attraction of gangs. An increasingly ideological education system failing to equip young people with the skills they actually need.

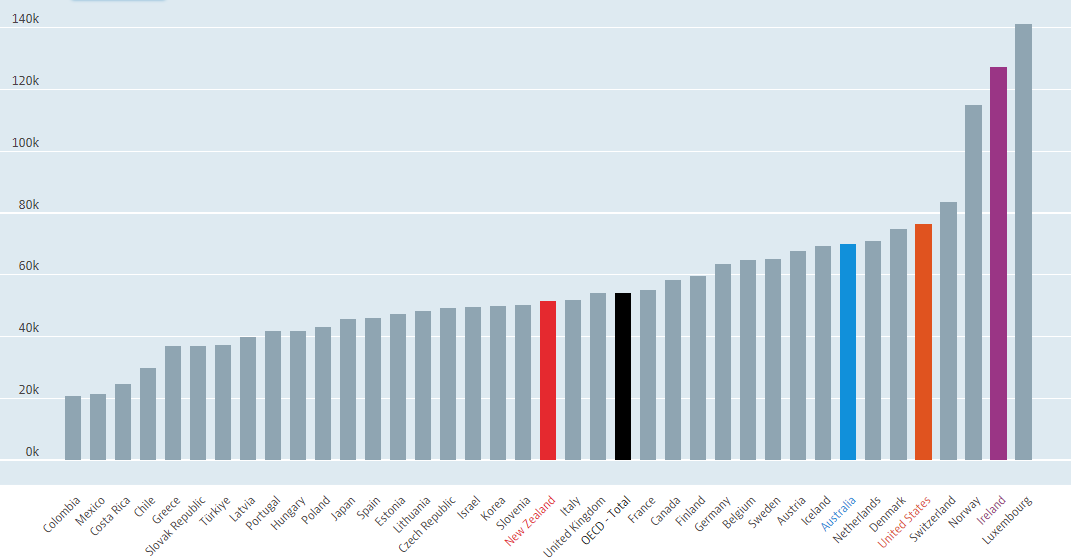

GDP per capita

The measure for a country’s prosperity is GDP per capita. Simply, it is the total GDP a country generates divided by the population.

It does not measure inequality, happiness, lifestyle, social cohesion or a range of other more subjective factors.

But in New Zealand, levels of inequality are in line with other OECD countries. So GDP per capita performance becomes a key indicator on how prosperous we are.

This level of prosperity is what funds the tax system. It provides the resources for pensions, healthcare, education, and defence. And spend in these areas is then measured and compared as a percentage of GDP.

New Zealand sits in the lower group of countries below the OECD average:

Source: OECD data — GDP in US dollars/capita — 2022 or latest available

Luxembourg’s GDP might be inflated. Its status as a corporate financial centre sees outsized foreign direct investment, much of it into corporate shells.

In the real world, for locals, GDP per capita as it manifests in household income could reflect lower.

Hold that thought.

On the above chart, there is also a startling comparison between two countries of similar population. Ireland and New Zealand. Irish GDP per capita is more than twice that of New Zealand’s!

Well, Ireland is part of the EU, you might say. It has a proximate market of over 400 million people on its doorstep. But I doubt that is the main reason.

Greece is also an EU member and has similar proximity. New Zealand is part of the burgeoning Asia-Pacific rim.

Let’s look at some of the economic and social forces that have catapulted Ireland to the top of the OECD’s wealth list.

There are many studies on the Celtic Tiger’s rise to prosperity. Digesting these, we come down to some key factors:

- Welcoming to foreign direct investment (FDI). A corporate tax rate of 12.5% (25% for non-trading income, e.g. rents). An FDI agency acting as a concierge to new investors — IDA Ireland.

- The availability of high talent. Ireland has a strong education system with teachers being well-paid. The top teaching scale — excluding responsibility units — is €75,871 ($135,200) v. $90,000 in New Zealand. Crucially, the country has a high percentage of 30-to-34 year olds with a tertiary qualification. It ranks first for attracting international talent.

- A very pro-business approach. ‘Green lights over red tape’ is the promised catchphrase.

Like New Zealand, Ireland has experienced high rates of migration following the pandemic to fill shortage occupations. Anecdotally, it would appear the skill level of migrants sought in Ireland is higher.

When you have large investments from international companies, it becomes possible to attract highly skilled migrants.

For example, Intel alone has invested more than €30 billion in Ireland, creating the most advanced industrial campus in Europe.

Intel Lexlip Campus, Ireland. Source: Intel

This is not to say that Ireland does not have issues too.

Given the outsized role that FDI plays, does GDP per capita translate to real prosperity for the average Irish household?

Unaffordable housing and rental shortages have been well publicised in Ireland. The average home price reached €359,000 ($639,738) at the start of this year.

Still, that is somewhat more affordable than in New Zealand.

The median household income in Ireland after tax is €46,999 ($83,754). With home prices being around 7.6x that.

In New Zealand, median household income after tax is $88,454. The median home price (June 2023) was $891,585. Home prices are 10.1x median household income in New Zealand!

So, Ireland has lower disposable household income than New Zealand?

Yes. Although Ireland has GDP per capita twice that of New Zealand — why does it actually end up with lower household income levels?

Ireland’s story and favourable comparison to New Zealand is not as ideal as some may think.

One reason for Ireland’s lower disposable household income is that income tax is much higher. 40% is levied on incomes above €40,000 ($71,280), with an average income tax on workers of 27.5%.

In New Zealand, that average tax on individuals is only 20.1%.

But this is not the only reason for the GDP to household income discrepancy.

Some of the Ireland-adoration in the local financial media needs to be addressed. For a country with GDP per capita twice that of New Zealand, why are household incomes (after tax) a fair bit lower?

A good part of Ireland’s GDP is produced and captured by foreign investment interests. The corporate tax rate is low. This could mean significant amounts of GDP generated in Ireland actually go offshore back to parent companies.

Further, some commentators suggest that Ireland’s GDP is overstated. Some of the multinationals based there may use the country for ‘profit shifting’. Again, we may see this with Luxembourg (at the top of the OECD GDP per capita table).

In 2018, the IMF reckoned that up to a quarter of Ireland’s GDP growth could be attributed to global sales of iPhones, with other Apple units paying the Irish unit to use its IP.

My own experience of living in another low tax jurisdiction was that high GDP per capita can be distorted. Life on the ground can be very different.

Ireland has more than 1,500 multinationals. including top tech and pharmaceutical firms. Due to revenue channelling (to take advantage of Ireland’s low corporate tax rate), GDP could be inflated beyond what is actually produced in the economy.

There is also a high tax rate on capital gains in Ireland. Not so in New Zealand.

It strikes me, for an aspirant investor or entrepreneur, it could be easier to make or build your fortune in New Zealand.

Personally, I wouldn’t like to live in Ireland. I’ve done one too many winters in Northern Europe. Further, local residents in Ireland seem heavily taxed with expensive energy bills. You’d struggle to grow a lemon tree, and washing hung outside would likely freeze solid part of the year.

There is a trade-off in laying down such a bright, shiny welcome mat to the multinationals. You get the skilled jobs and the investment. But you don’t necessarily get the real prosperity from locally produced innovation and exports.

Don’t get me wrong. Ireland has been extraordinarily successful. And there likely is a correlation between teacher pay, foreign investment, less red tape, and GDP per capita — and how all that creates prosperity and cohesion in society.

On that note, Ireland is currently tracking to be a bit safer on the crime front.

I couldn’t find any reporting of shootings this year.

Homicide is a key metric, since the seriousness of this crime means all incidences get reported. Ireland had 39 murders in 2021; New Zealand 52.

Both countries have similar levels of policing. But if you look across the last five years, the numbers converge to be more similar.

Perhaps the more concerning times we face in New Zealand is a recent phenomenon?

New Zealand will forge its own path. It has the basis in place to generate local innovation. And has competitive advantages in food production.

This country needs to work on those key issues of housing cost, lack of investment, productivity, and social cohesion.

There are levers that can be pulled. They will require hard decisions, trade-offs, and taking some risks.

For investors, we find the one free lunch in finance is diversification.

From New Zealand to Europe to North America, we scour the global markets for value and opportunity.

In our Quantum Wealth Report, we cover the markets, industries, and companies that are progressing at the top of their game. From the NZX to the FTSE to the NASDAQ…

Try this Premium Subscription today for analysis and reporting you won’t get anywhere else.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is the editorial content of this periodical. It is the author’s personal opinion and commentary. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. For the conversion from EUR to NZD, an indicative rate of 1.7820 was used.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.