Duty. Obligation. Shame.

You could say that this is what sets Japan apart from most other countries in the developed world.

Why is Japan so unique?

Source: Biblio

In 1946, Ruth Benedict published her landmark book, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. She was the first Westerner researcher to do an in-depth study on Japanese culture.

She described it like this:

Both aggressive and unaggressive, both militaristic and aesthetic, both insolent and polite, rigid and adaptable, submissive and resentful of being pushed around, loyal and treacherous, brave and timid, conservative and hospitable to new ways.

It’s a fascinating observation.

If the language that Benedict used doesn’t sound inclusive by today’s standards, well, you have to remember: she did her research mainly during the Second World War.

At the time, most Westerners regarded the Japanese as mysterious. Inscrutable. Unknowable.

So Benedict’s goal was to break down the walls of misunderstanding. Present a more well-rounded picture of Japan. This wasn’t just a matter of academic interest, but a matter of urgent foreign policy.

In the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan had surrendered. And the triumphant Allies inherited a devastated nation:

- Nearly a third of the country’s wealth had been destroyed by bombing.

- Urban living standards had declined to 35% of pre-war levels.

- Disease and starvation were rife.

Yes, the situation was grim.

The Japanese emperor, Hirohito, called on his people to cooperate with the Allied occupation:

‘The hardships and sufferings to which our nation is to be subjected hereafter will be certainly great. We are keenly aware of the inmost feelings of all of you, our subjects.

‘It is according to the dictates of time and fate that we have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is insufferable.’

This was a defining moment.

Indeed, enduring the unendurable became a rallying call for what the Japanese needed to do in order to rebuild and recover from the ashes of war.

Source: Amazon

Historian John W. Dower, in his book Embracing Defeat, sums it up like this:

The losers wished to both forget the past and to transcend it.

The ideals of peace and democracy took root in Japan — not as a borrowed ideology or imposed vision, but as a lived experience and seized opportunity.

The economic miracle

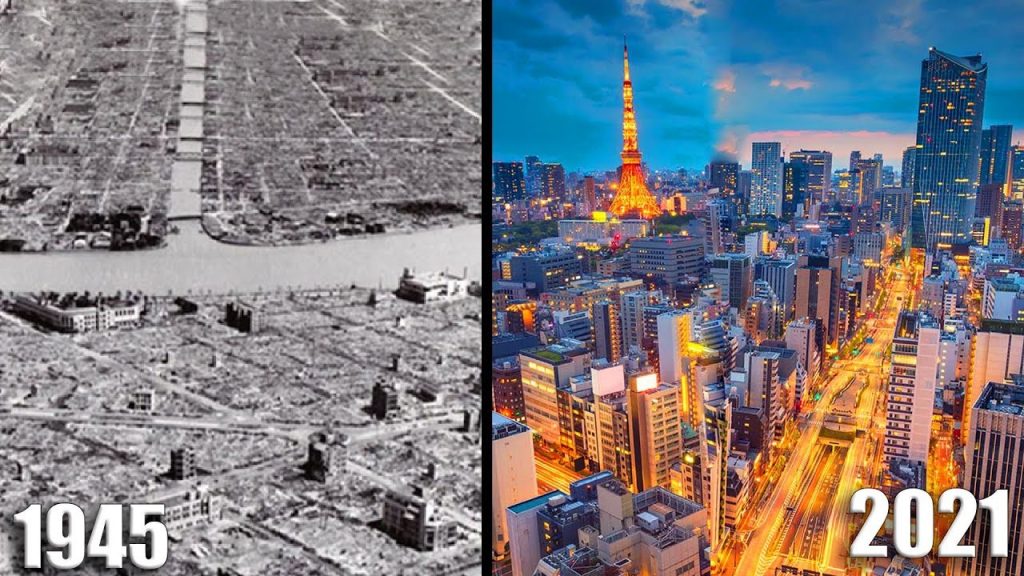

Source: YouTube

So, how do you transcend defeat and reinvent yourself?

Well, Japan’s journey offers an intriguing answer.

Its transformation from a shattered nation in 1945 to a rapidly industrialising power by the 1960s was nothing short of stunning.

In fact, during that time period, Japan actually had one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world. It peaked at 12.9% in 1969.

Seemingly overnight, Japan had gone from being a hated enemy of the West to being a close ally. Indeed, Japan had become the poster child for American-led capitalism.

From cars to microchips, from video games to anime, from sushi to karate, Japan was not only a manufacturing behemoth, but a cultural wonder as well. This was helped, in no small part, by trade policies that favoured the nation.

But, soon enough, Japan’s ascendency began to rattle American nerves.

Source: Penguin

Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun captured this feeling of collective anxiety very well.

Japan was perceived to be a keen student of capitalism, expanding aggressively, and it was now on the brink of eclipsing the master, America.

Yes, Japan may have lost an actual war against America. But — surprise, surprise — it was now apparently winning the economic war.

This negative sentiment even fed into street crime.

In 1982, the car industry in Detroit was in trouble. Japanese imports were cutting into American manufacturing. Jobs were being lost. The mood was sour.

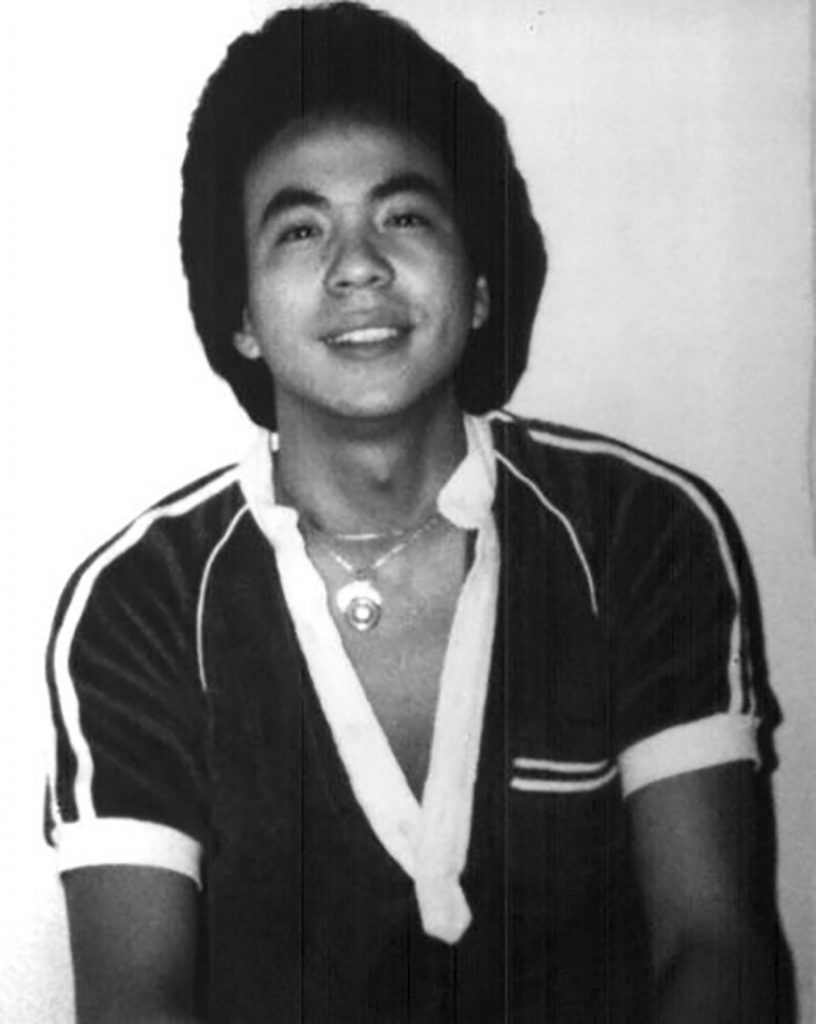

This was when Vincent Chin, a draftsman, encountered Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, two autoworkers, in a strip club.

An argument soon broke out about tipping a stripper.

In the heat of the moment, Ebens reportedly said:

‘It’s because of you little motherf*ckers that we’re out of work.’

Fuelled by alcohol, the altercation quickly escalated. Punches were thrown. The fight spilled out into the street. A baseball bat was retrieved and used.

Tragically, Chin ended up dead.

Source: NBC News

The irony here is that Chin wasn’t even Japanese. He was Chinese. Clearly, he had gotten involved in the wrong argument, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.

The case would remain haunting for the Asian-American community, due in no small part for its sheer senselessness.

Nonetheless, the volatile emotions would soon become a moot point. Because, from 1986 onward, Japan’s bubble started to pop — and the country went into a stagnated crawl that it never quite recovered from.

Elevated asset prices. Excessive debt. Overly easy credit.

When a correction happened, it spelled the end of the post-war economic boom.

The aftermath

From 1991 to 2003, Japan’s economy grew by just over 1% annually.

This was considered a Lost Decade. A stunning reversal from the high growth rates that the country used to enjoy.

In the aftermath, the fabric of Japanese society itself appears to have become unstuck. You have to remember: this is a culture where work is highly prized and gives a source of purpose and belonging. But job security is no longer what it used to be.

This has given rise to an issue known as jouhatsu — evaporating people.

Reportedly, over 100,000 people vanish in Japan every year.

Why does it happen?

It can be summed up with one word: shame.

Source: News NCR

The New York Post investigates the story of a Japanese man named Norinho.

When he lost his job as an engineer, he was so ashamed that he couldn’t bring himself to tell his family. So he carried on with his usual routine of dressing up each day and leaving home, pretending to go to work.

He would roam the city for hours.

Then he would pretend to come home from work.

But after a week, he could no longer keep up this false pretence.

So Norinho made the decision to vanish:

On what would have been his payday, Norihiro groomed himself immaculately, and got on his usual train line — in the other direction, toward Sanya. He left no word, no note, and for all his family knows, he wandered into Suicide Forest and killed himself.

Today, he lives under an assumed name, in a windowless room he secures with a padlock. He drinks and smokes too much, and has resolved to live out the rest of his days practicing this most masochistic form of penance.

“After all this time,” Norihiro says, “I could certainly take back my old identity . . . But I don’t want my family to see me in this state. Look at me. I look like nothing. I am nothing. If I die tomorrow, I don’t want anyone to be able to recognize me.”

Norinho’s story is shocking, but it’s not isolated.

It’s part of a wider trend within Japanese society:

Another case, unresolved, involved the young mother of a disabled 8-year-old boy. On the day of her son’s school musical, in which he was performing, the mother disappeared — despite promising the boy she’d be sitting in the front row.

Her seat remained empty. She was never seen again. Her husband and child agonize; the woman had never given any indication she was unhappy, in pain, or had done something she thought wrong.

Absolutely heartbreaking.

Indeed, people can vanish for reasons that are seemingly minor. For example, failing a school exam can be a reason for someone to evaporate.

The New York Post sums it up:

In many ways, Japan is a culture of loss. According to a 2014 report by the World Health Organization, Japan’s suicide rate is 60 percent higher than the global average. There are between 60 and 90 suicides per day. It’s a centuries-old concept dating back to the Samurai, who committed seppuku — suicide by ritual disembowelment — and one as recent as the Japanese kamikaze pilots of World War II.

Japanese culture also emphasizes uniformity, the importance of the group over the individual. “You must hit the nail that stands out” is a Japanese maxim, and for those who can’t, or won’t, fit into society, adhere to its strict cultural norms and near-religious devotion to work, to vanish is to find freedom of a sort.

Duty. Obligation. Shame.

Japan is a country where tradition and modernity collide, and it is a society struggling to deal with a shifting social landscape.

Indeed, it is common for Japanese people to internalise psychological trauma. To quietly bear emotional burdens. To never speak of them.

Unfortunately, this has also led to another issue known as hikikomori — extreme social withdrawal.

Source: Wall Street Journal

These people do not vanish, but they choose to hide themselves away. They become hermits. Unable to cope with the pressure of society’s expectations.

It is estimated that at least a million people in Japan live like this. They do not study. They do not work. They do not socialise.

They live in an isolated cocoon at home. Completely detached from the world at large.

This is a tragedy, unravelling in slow motion.

The bottom line

There is much to admire about Japan.

Its people are polite and diligent.

Its society is orderly and largely crime-free.

Its transformation from fascist enemy to democratic ally is remarkable.

But, clearly, Japan is wrestling to find a sense of direction in the 21st century. Its monocultural experience — bereft of immigration — may be a weakness. So is its ageing population and low birth rate.

Even so, it would be a mistake for us to dismiss Japan’s potential. It is the third-largest economy in the world. It is a market leader in vehicles and electronics. Indeed, it remains a potent force to be reckoned with.

So, can Japan transcend its deep melancholy and reinvent itself once more? What does it need to do to achieve this?

That’s the $5 trillion question.

Only time will tell.

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.