As wholesale wealth managers, it’s fair to say that when it comes to wealth in New Zealand, we see the top 10%.

They’ve made money in business, property, or from years of diligent saving. They’re thinking people who want to continue to protect and grow their wealth.

Property has been a big generator of fortune. But that super-cycle looks about to be coming to a brutal end. Something I’ve been warning of for the past few years, copping a lot of flak for doing so.

At the moment, we’re seeing quite an aggressive bear market clawing away wealth in the financial markets. This last month has been so bloody, you can pretty well taste the fear.

The property people will say: ‘At least I’ve got my money in a roof over my head, or rentable land and buildings. Those values won’t fall too much…and I’ll only lose if I have to sell.’

A ‘ghost estate’ of unoccupied homes in Ireland, circa 2010. Irish house prices fell 54% from 2007 to 2013.

Source: Daily Mail

Receiverships stall house settling in Ormiston, Auckland.

Source: DDL Homes

Unfortunately, wealth held in property is starting to sink.

Given its size in this economy, that has wider ramifications.

But we’ll get to that…

As for the bear market in equities…

Is it going to get worse? And how long will it last?

Seeing profits turn to loss in a brokerage account is painful. We’re invested in the same strategy as our clients. You eat your own cooking in this business.

Life and investing are far from problem-free. But a paper-loss in a bear market that might only endure for a period of time is not the end of the world.

When pernicious problems do arise, I recall teachings from one of the most powerful books I’ve ever read.

Man’s Search for Meaning. Viktor Frankl.

Frankl somehow survived the Nazi concentration camps.

The lasting message I took, and try to operate by, is this: any situation can be improved by positive action.

Selling during a market low, unless you absolutely need the money, will probably be a negative action.

People in countries like New Zealand, especially in the wealthiest 10%, sometimes suffer a little ‘comfort damage’. They’ve mainly seen asset prices rise. They’ve mainly lived a comfortable life.

Not all are mentally prepared to deal with the highly uncomfortable feeling of loss, however transitory.

You instinctively see this. Immigrants from more troubled lands often make great investors because they’ve spent half their life managing loss and renewal.

Positive action when the outlook is fearful

The positive action I’m taking in this bear market is to buy shares in quality companies at sharp prices. Having been through a few market cycles, I know these opportunities don’t come along very often.

Yet there’s a painful risk riding on this strategy.

What if this bear market runs for years? Think of the ’70s. Or Japan’s Lost Decade.

But history is on our side. Most bear markets are much shorter than bull markets. Cash has to eventually find a productive home again.

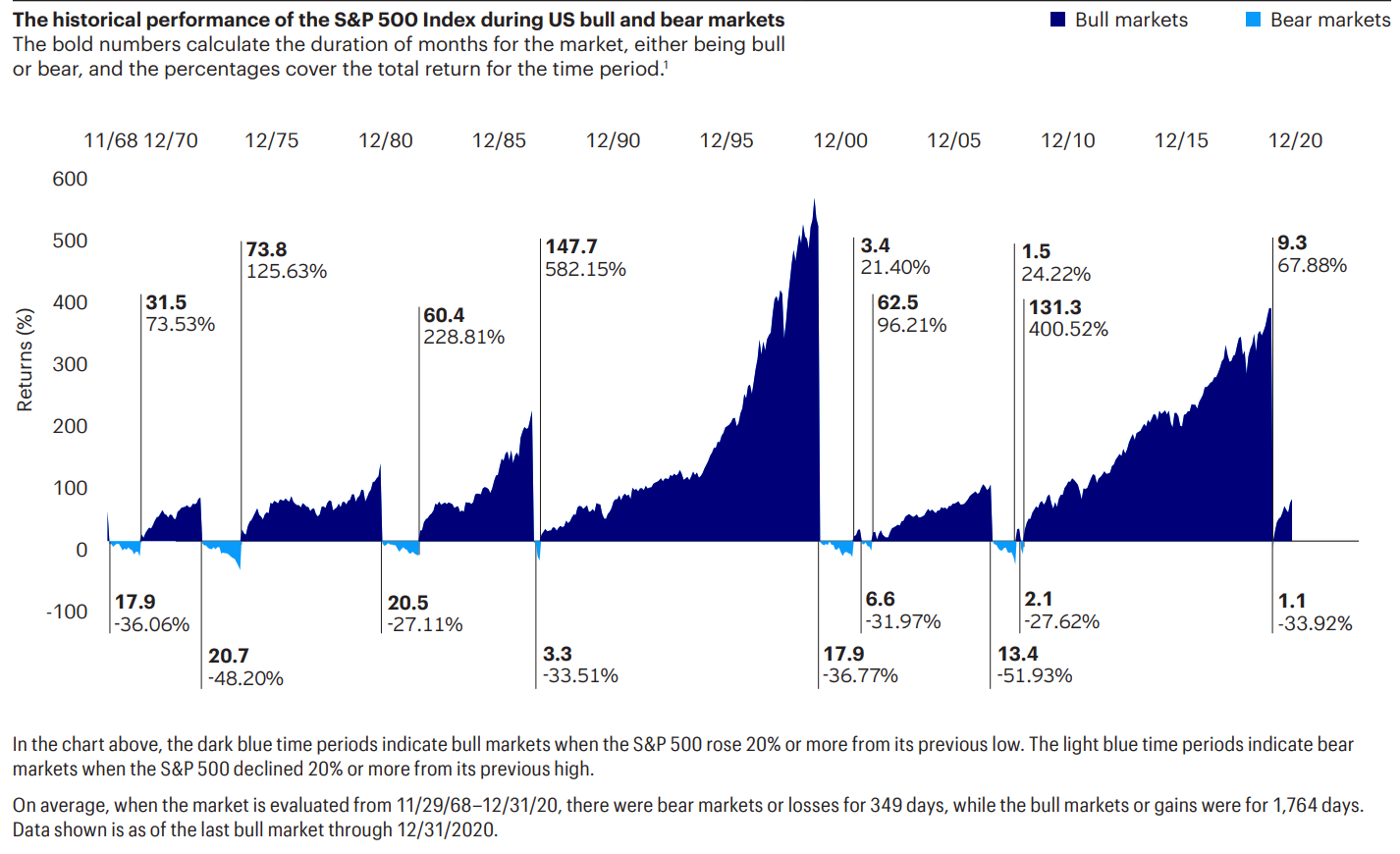

A study from Invesco of S&P 500 performance since the 1960s found that bear markets on average last not more than 11.7 months, with an average loss of –34%. But bull markets lasted 55.1 months, with an average gain of 154%.

Source: Invesco

These days, markets are more fluid. I contend we could bounce out of bear markets faster.

But isn’t the world more unstable than ever before?

Isn’t the global world order, based on US hegemony following WWII, now facing existential threats on many fronts?

Let’s briefly examine the risk events…

Inflation and a credit crunch

Quantitative easing was used to soothe pandemic lockdowns. Economies are dealing with the after-effects of loose monetary supply.

At the same time, they have to deal with an interest-rate shock. An oil shock. And, still, the tail end of a supply shock.

Growing up in the 1970s and ‘80s, this seems very relative.

Petrol became so scarce, there were carless days. My father followed a government initiative to convert the family car to CNG.

In the mid-‘80s, variable mortgage rates hit 20% here in New Zealand. I recall taking up a term deposit with the National Australia Bank at 16%.

But in real terms, we were still scrambling.

Today, variable mortgages might be around 5.8%.

This is not too far from the historic average interest rate since 1311 AD of 4.78%.

Sure, they may go higher. And it is a shock, since for some, rates have effectively doubled.

Yet the outlook for equities may not be as bad as many think.

Many of the companies we follow and invest in are showing increasing earnings. Some have too much capital. So are buying back shares and increasing dividends. But the stock prices are often still being caught in wider market malaise.

Maybe they’re being oversold.

Now central banks are being responsive. A little late for some. But it does seem they can reduce price growth. Without destroying employment.

We’re already seeing home prices fall. According to The Economist, declines in microchip, shipping, and fertiliser pricing suggests inflation may have already peaked.

Sourcing fuel beyond Russia is going to take more time. OPEC has already agreed to speed up production. Biden is calling for local American refiners to ramp up production. In fact, US oil production is forecast to surpass its 2019 record in 2023.

Ukraine, Taiwan, and a new world order?

From all the reports we have, it seems Putin might have bitten off more than he can chew. The bargaining position has been skewed by united support for Kyiv.

This ‘special military operation’ seems to have encouraged more NATO enclosure of Russia. Not less. Now the European Commission is backing ‘candidacy status’ for the Ukraine to begin the process of joining the EU.

As the war continues to unfold, it is likely both parties will reach a situation where talks are the logical way out. No doubt, Ukraine hopes counterattacks will strengthen their position.

This is an ongoing concern, especially for European markets. But it is a localised conflict that has some hope of ending.

Meanwhile, by my analysis, China’s success story ran from 2001 (when it joined the WTO) to about 2021. Then the follow-on effects of the pandemic, high rates of debt, and its demographic profile began to hit home.

China is not a country able to feed itself. It takes about an acre to feed the average consumer. China only has 0.2 acres of arable land per citizen.

By definition, modern China needs open trading waters to import the food and input materials it needs. And to export the industrial production it uses to pay for those.

America, for many decades, has helped China to prosper. It has kept shipping lanes — particularly through to the oil states — safe and navigable. And it has provided a significant market for China’s goods.

If China wishes to change the status quo on Taiwan, it currently faces so many threats, the whole gambit seems illogical.

Source: Foreign Affairs

First, there is the simple matter of trade to and from China likely being cut off for an extended period of time. Food and inputs cannot get in. Even if customers in America or Europe might accept any Chinese products — and chances are, they would sanction them — exports may not be able to get out.

Second, while the level of direct support America may offer Taiwan is unknown, there are powerful, vested interests in the region.

Japan and South Korea both rely on key shipping routes by Taiwan. While Japan’s constitution only allows for military action in ‘survival-threatening situations’, a Chinese takeover of Taiwan could qualify.

All this seems like a chess move. Trying to take a strategic piece that may be defended by rooks and a fast-moving queen. The board is not sitting right.

Then there’s the question of the state of China itself. The economy is slowing. The population is ageing fast. There are some 35 million more single men than single women. Total debt, which has driven the multi-decade record expansion, is almost 3x GDP. House prices are falling.

It looks hard enough to maintain the current system, let alone venture into Taiwan.

The NZ property market

The global outlook has upside in the recovery of corporate earnings. But the outlook for New Zealand and Australia looks more tenuous. Much of the growth we’ve enjoyed over the past two decades has come from supplying China.

The New Zealand housing market is such a dominant form of wealth in this country, any major drawdown could be devastating. The ‘wealth effect’ could dry up, as people see hundreds of thousands of dollars erased from their valuations.

Auckland has also benefited — as many Pacific Rim countries have — from an outflow of money from China. Much of this has gone into the housing market via loose immigration. That money is still circulating.

As one agent noted: ‘The CV or RV doesn’t matter, streets like Arney Road, Arney Crescent and Victoria Avenue [in Remuera] are very famous for local Chinese buyers.’

Whether there will be more money from China to flow into New Zealand remains much more uncertain in this environment.

Arguably, such investment into the housing stock, rather than in productive business, causes more harm than good.

If the Chinese economy continues to stumble, this will have ramifications for Australasia. These housing markets are already showing signs of debt distress.

The bottom line

Look beyond property.

Look beyond fear.

The wider outlook suggests a global bear market in equities may not run as long as we may think. The risk events seem resolvable. Or unlikely. There will be a new hope.

Provisos: I am an optimist. I assume people act rationally. Sometimes they don’t.

For now, the rational choice for me and our clients is to buy value in the markets when we see it.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo is a portfolio manager at Vistafolio.

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.