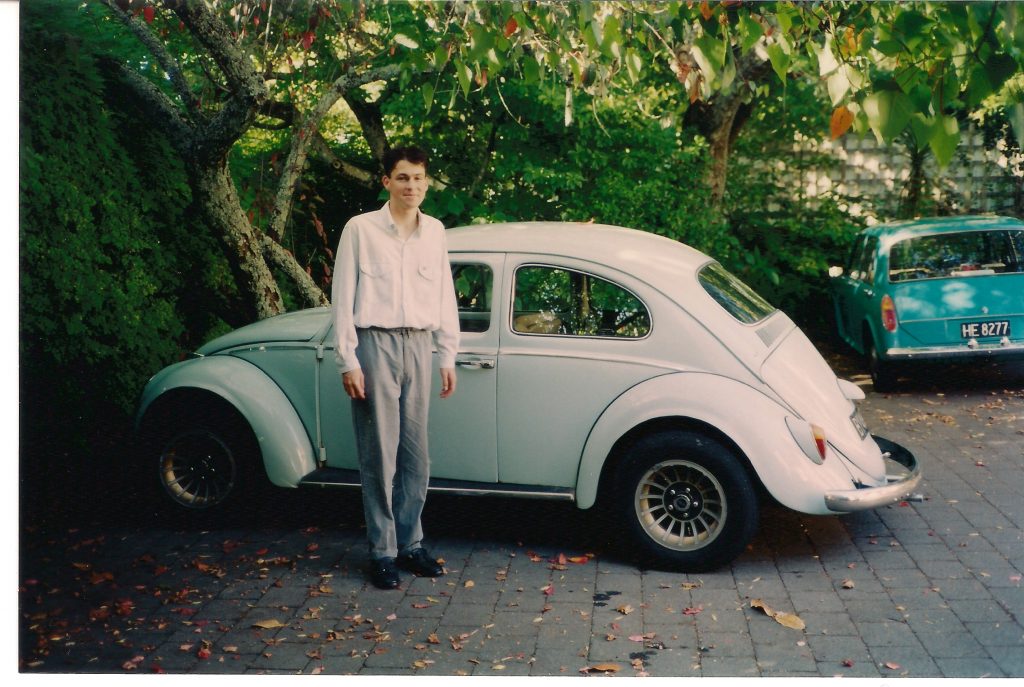

My first car was a 1967 VW Beetle. A beautiful car. An air-cooled engine.

But, from time to time, that engine would overheat on the long road between Taranaki and Auckland. Then it would cut out. The only remedy was to pull over and let the engine cool awhile. So you could get going again.

Of course, you would need to watch for signs of overheating. Should the engine cut out on the winding hill climbs making up part of your journey, you could end up in some trouble. The most reliable sign was by smell.

Simon’s ’67 Beetle. Source: Author

I thought of this the other day when I walked past another Beetle. This one probably circa 1974. And I wondered if our after-Covid economy had reached a similar situation of overheating.

Could now sky-high asset prices seize up? Need a long period of cooling?

The lockdowns in Auckland have been tough. Human brains need more stimulation than this situation allows. Starve the hippocampus from different places, people, and experiences, and you can soon find yourself at risk of anxiety or depression.

By contrast, financial (and housing) markets have been over-stimulated. As governments and central banks fret over financial fallout, they have poured loose money into the economy:

- Record-low interest rates.

- Large-scale asset purchases (bond buying).

- Helicopter cash in the form of wage subsidies and resurgence payments.

In some ways, this is the equivalent of treating your mental health with a plethora of wine.

Temporary relief, certainly. Enjoyment — if the wine is good.

But overdo things and you can set yourself up for other health issues and even dependency.

Has the economic response to Covid-19 overdone things?

Has it smothered anxiety over property and financial markets with a nightly bottle of red?

And if so — what will the fallout be?

Home prices

New Zealand, like other countries that have turned on the stimulus tap, has seen rampant run-ups in house prices.

US metropolitan home prices rose 18.6% for the year to June 2021. The highest annual growth rate since the index began in 1987.

In a much smaller, more fluid economy, ours’ have exceeded even these dizzy heights.

Of course, home prices can never come down! They are defensive, robust — and besides, there are desperate shortages.

Or will this time be different?

The 1970s

When I was growing up, my parents tell me, it was still a major struggle to enter the housing market. They returned to New Zealand from Europe in the early 1970s.

We were in the middle of the oil shock. This saw input prices across the economy (transport, production, and more) jump. It led to stagflation. Rising prices without the ability to increase output and jobs.

There was a new approach to transport then. Dad had converted our car to CNG (compressed natural gas) following government incentives. You flicked a James Bond-style switch beneath the steering wheel to change your fuel source.

These days, the new fuel source is batteries. Will they be another CNG? A nice idea — but never to fully deliver on the expected efficiencies to a high enough degree?

As for the economy and prices, I see a similar thing now. This time, the price shocks are not coming from oil but from freight, shipping, and disruptions. Prices are rising fast. Yet many businesses are constrained in their ability to produce any more.

From 1972 to 1974, we saw house prices jump. The curve then was as steep as we’ve recently seen it now in 2020 to 2021.

Then as now, people turned to housing as a defensive investment. It was the one place they thought they could protect themselves from the price shock. Building ramped up. Land sales reached fever pitch.

But from 1974, things turned very different. From 1974 to 1980, house prices fell around 40% in real terms. They didn’t fully recover until 1996 .

Housing markets have long cycles. Unlike stock markets — which may face major corrections every decade or so, then recover in a year or two — housing markets can fall into deep corrections after 25 years or more.

The falls can be large, especially when exacerbated by debt. And the recovery time can span decades.

Could this be the real cost of Covid and the hefty response to it? Overheated asset markets sitting perilously at risk of drawdown?

We know how inflation goes. A small amount can be beneficial, even stimulatory. But if it goes too far, gets away, and production cannot respond, things can end up in a dark place indeed.

For now, we can only watch and wait.

But it is Friday. So I shall open a nice Aussie red to go with dinner. This will get us through the worries of the moment.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.