It’s early evening. I’m walking along the Devonport waterfront with a friend who lives nearby. He points out some vans and a station wagon parked up on a car park.

‘They pretty much live here,’ he tells me. ‘There’s usually 5 or 6 here. Using the nearby public toilets.’

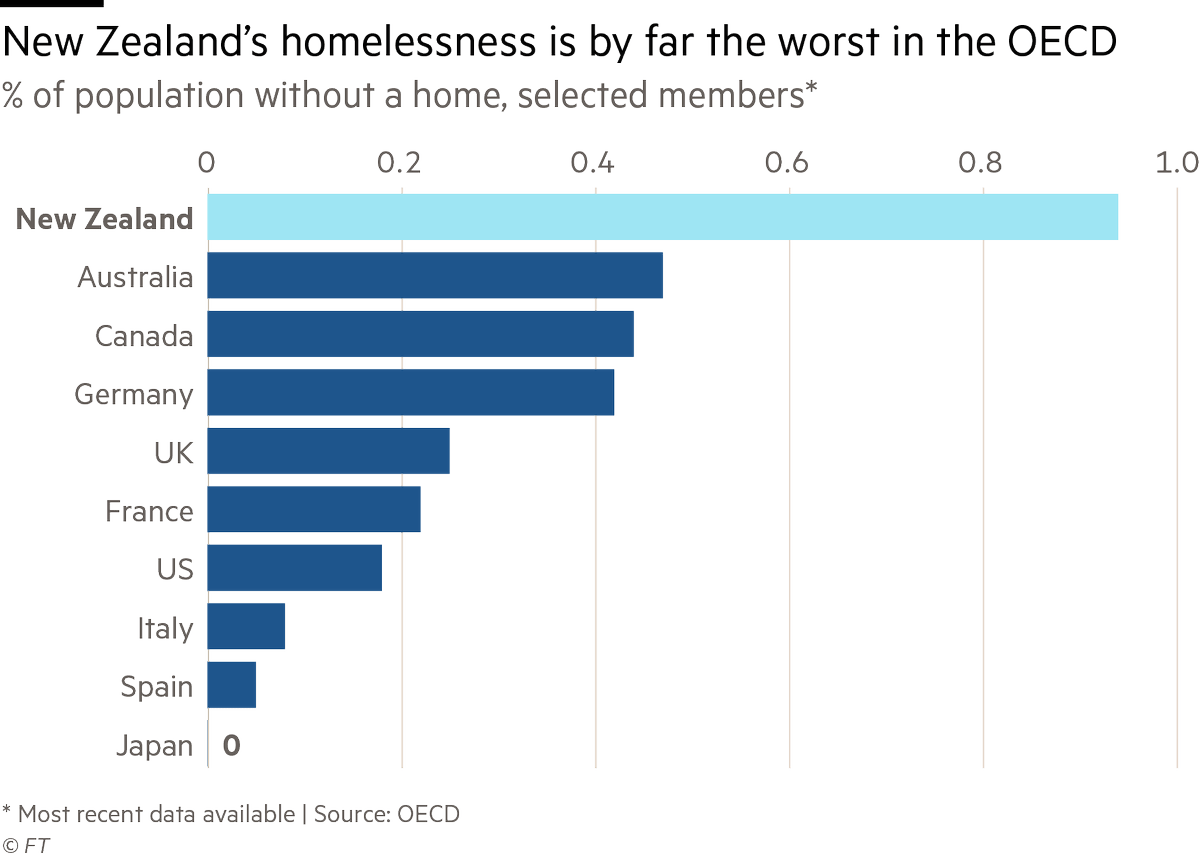

I see homeless people around the central city and have done for years. But I wasn’t aware that this was spreading to the suburbs. And even towns as far away as Warkworth.

The true extent of homelessness it not always visible. It is in vans and cars. In people temporarily ‘crashing’ with family until they outstay their welcome. And in government-funded boarding hostels and motel rooms, often inadequate for families.

Source: Brendon Harre, Medium

But this is not the first time I’ve encountered a car as someone’s only available roof.

We recently spent some time on the Channel Island of Jersey. Housing there is in such short supply the government operates a housing-licence system.

Unless you’ve lived on the island for many years, to buy or rent a decent family home, you will need a licence. These are only issued to ‘essential employees’. To keep such a licence, you must also remain an essential employee.

I came across a woman who was married to a local resident — entitled to own or rent a house. When her marriage broke down, she lost all access to housing. And ended up living in a station wagon through the brutal European winter, trying to keep her two children in school.

Jersey has some of the worst drug, alcohol, and mental health problems I have seen anywhere. For a supposedly wealthy place. At the root of this is insecure and inadequate housing.

Source: Channel 103, Jersey

Homelessness and housing affordability is also a problem in the UK.

But after returning to New Zealand, the problem seems worse here.

But this is not surprising. Even after strong post-pandemic growth, the UK average home price reached a peak of only £252,000 (NZD $486,360) in December 2020.

In New Zealand, the average price was $788,000 in December 2020.

But here’s the rub. The median rent across NZ was $520 per week in November 2020. In the UK, the average monthly rental was £868 per month for private rentals. This implies a weekly rent of only NZD $386.

It is clear New Zealanders face higher housing costs and often lower wages compared with a country far more densely populated.

The failure stops here

Source: The New York Times

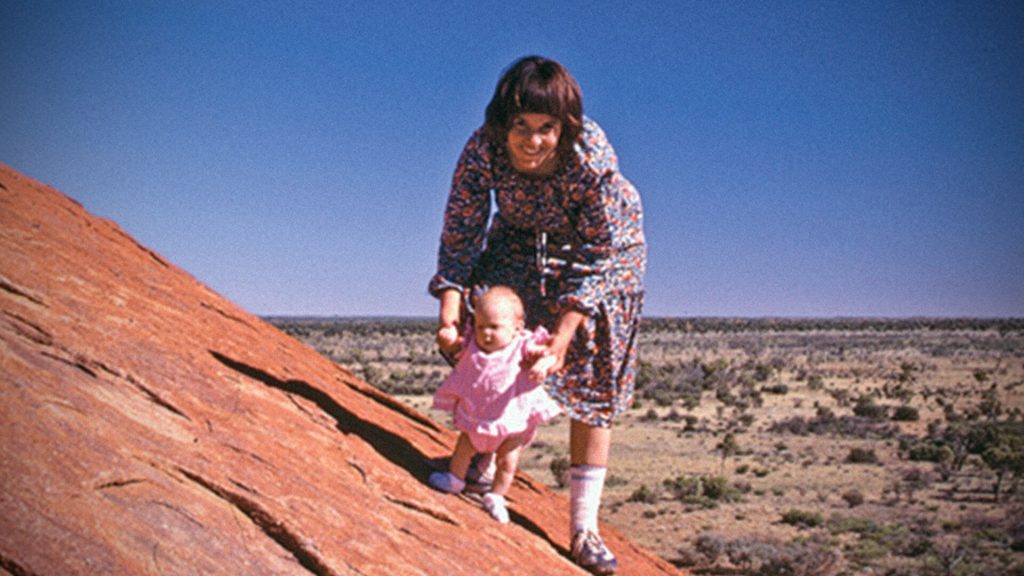

Last week, I found myself glued to the TVNZ documentary ‘Trial in the Outback: The Lindy Chamberlain Story’.

Growing up in the 1980s, Lindy’s devastating case was everywhere. On the news. In magazines. Discussed in worried tones by the adults around me.

New Zealand-born Lindy was wrongfully convicted for killing her baby Azaria. She was sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour in 1982. On the back of what appeared to be a shoddy trial in the remote Northern Territory of Australia.

Despite public opposition and alleged persecution on account of her Seventh Day Adventist Christian faith, a band of courageous supporters formed to fight Lindy’s case.

In 1986, new evidence was found. After intense fighting and public support, Lindy’s conviction was quashed in 1988, and she received $1.3 million in compensation in 1992.

In 2012, a fourth coroner’s inquest found that Azaria died ‘as a result of being attacked and taken by a dingo’.

I mention Lindy’s story because it is an example of how very wrong governments can get it.

Judicial systems can fail with devastating consequences. And destroy lives.

Economic systems can also fail and damage lives. Which is our focus here.

The New Zealand housing market exhibits clear signs of economic ‘market failure’.

The classic explanation of market failure used to be ‘a factory that creates jobs and wages. But then goes on to pollute the environment’.

In this case, the process of generating economic value creates negative externalities.

We see the same in the Kiwi housing market. Many investors buy homes for rental yield income and capital growth over the longer term.

As a small, open economy, there are also significant inflows of foreign cash from migrants and offshore family members. Often from fast-developing, savings-rich parts of the world such as China.

While investment into the housing stock appears positive, it has severe negative externalities. In that we now have too many buyers for too few homes.

Good government should address miscarriage of justice. And economic market failure. That is its job. But for around 20 years, it has failed to do so.

Instead, such government appears to have been harmful to younger people looking to get a foot on the property ladder. And the increasing number of people struggling to afford very high rents.

Meanwhile we see investment into businesses and productivity lagging. Due to outsized investment into second-hand housing.

In America, the wealthiest sectors of society hold their money in financial assets like stocks and shares. In New Zealand, we see far more concentration of wealth in housing assets.

We are building an alternative plan. And have a petition backed by investment-grade analysis to try and get government to do something. It is not something we get paid to do. But something we do to try and help fight this crisis.

You can review our plan and sign the petition here 👉 TheKiwiDream.nz

Investing in housing

Many investors we speak to are now wondering if they should exit rental property. Or buy another.

We have no crystal ball, and in any case, cannot provide any personal advice.

What we are starting to see are investors with multiple properties starting to quit them. The reasons given are an unusually high market. And increasingly burdensome landlord regulation.

But what I would say is that the risks around property investment in this country are far higher than they’ve been before.

- There is now clear risk of more government intervention in the housing market.

- High prices appear supported by high debt (not high wages). Mortgage interest may get repriced in the medium-term.

- Due to rising capital values, many rental yields are now very low on a net basis (after all costs), sometimes below 2%.

- Covid has slashed net migration. There are signals government may take a reduced approach when borders reopen, instead focusing on upskilling New Zealanders.

- Loan-to-value and debt-to-income curbs look set to embed, reducing debt flow into the buy-to-let market.

- Supply is coming on stream at larger scale, though shortages do remain in some areas.

My approach, beyond a home, is to invest outside of this country. In global businesses with quality assets, sitting at value.

This approach has thus far yielded better income and similar growth to local property investment. Without the stress that goes into managing tenants. And with superior diversification.

If you qualify as an Eligible or Wholesale Investor under the Financial Markets Conduct Act (2013), this may be a strategy you can also access through our Managed Accounts Service.

Here at Wealth Morning, we’ll keep fighting for smart investment. And fair market access. The prosperity of this country depends on it.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Please note: This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any security, or the suitability of any investment strategy. For advice to suit your unique situation, please consult an authorised financial adviser.

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.