US interest rates are all the rage.

The US bond market is finally moving in the direction that multiple bond bears predicted.

Bond yields are rising. The yield of a bond is its annual coupon payments divided by its prices. Because coupons are fixed, rising yields are associated with falling prices.

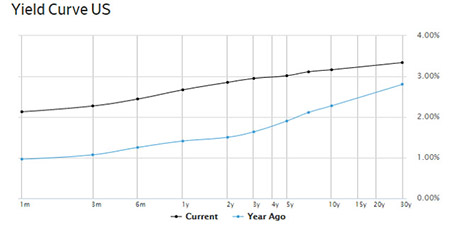

Across the board, from one-month to 30-year bonds, yields are up from where they were a year ago — which is to say, prices are down.

|

Source: The Wall Street Journal |

What does this means? It means investors believe inflation will be higher in the future. And they want to earn a return in excess of that.

For example, if investors expect long run inflation to be 3%, then they might want to earn a return (yield) of 5% on their bonds.

High inflation is also why the US Federal Reverse is pushing up interest rates. They’re limiting banks’ ability to create credit, which means there will be less money in the economy. Ideally, this will put a brake on prices rising too quickly.

On the other side of the globe however, the opposite is happening.

China isn’t dreaming of increasing interest rates. In fact, China’s central bank chief said they might even cut them if needed.

‘We still have plenty of monetary policy instruments, in terms of interest rate policy, in terms of RRR (required reserve ratio),’ Yi Gang, head of the People’s Bank of China said.‘We have plenty of room for adjustment, if we need it.’

And these aren’t just empty words.

Earlier this month, People’s Bank of China said they would cut the RRR. This means banks can hold fewer reserves with the central bank and lend more out to the public. Reducing the RRR by just 1% frees up about US$110 billion.

Why would China want to cut interest rates?

The general rule is high interest rates slow an economy and low interest rates speed it up. China’s priority is the latter. They want to grow and keep growing at rates like 6.5%.

To most, this seems foolhardy.

You can’t just pump more credit into a system already chock full of it. What will debt laden companies and households do when interest rates finally rise? A lot might go bust.

Even worse, what if inflation gets out of hand due to money creation? The millions of people who don’t own assets could see their wealth evaporate.

Pumping more money into the system seems like a bad idea any way you slice it.

But how do you think countries like China, South Korea and Japan grew in the first place? A lot of it had to do with money creation. [openx slug=inpost]

Professor Richard Werner explains (with my emphasis):

‘When bank credit is used for productive investments, such as the implementation of new technologies, measures to increase productivity or the creation of new goods and services (whose value is higher than the mere sum of their inputs, thus adding value), then such new money creation – which always happens when banks grant credit – will not result in any form of overall inflation – neither consumer price inflation nor asset price inflation.

‘This is because the new purchasing power that is created is used to produce higher value added output and hence the extra demand due to the money creation is met with a higher supply.

‘By ensuring that money and credit are only created when something real is created, i.e. for productive purposes, one can achieve very high economic growth without inflation, without crises and in a relatively equitable way: This is how the East Asian ‘miracle economies’ of Japan, Taiwan, Korea and China, developed so quickly.

‘By using regulation to ensure that bank credit is only created for productive purposes, high growth can be achieved, even when the economy is already at an apparent ‘full employment’ level, because productive investment credit improves the allocation of existing resources, however limited, by mobilizing both supply and creating the necessary demand for the output.’

OK, but isn’t this central planning? Something we’ve seen fail under communism time and time again?

Yet this is how most, if not all banking systems are set up.

A central bank at the top controls the rate at which banks can borrow and the level of money they can create. Werner is just proposing that banks create money for productive purposes, rather than speculative or consuming activities.

However, if China really wanted to secure growth, funnelling money into productive activities isn’t enough. There’s a longer term issue on the horizon, requiring a very different solution…

People QE

From Business Insider Australia:

‘In the north-western Shaanxi province, authorities have suggested dropping all limits on children and introducing financial incentives to “increase desire to procreate,” and the National Health Commission has researchers reportedly looking into whether tax breaks and other financial incentives would help encourage more people to become parents.

‘Baby bonuses, which have been paid out in countries like Estonia and Australia, are currently being offered in the city of Xiantao, where parents receive 1,200 yuan ($US177) for having a second baby.’

Why are babies important?

Firstly, a young population keeps the economy running. They’re the ones earning money, adding to business productivity and creating new goods and services.

Second and more important, future generations are the ones driving technology creation and innovation.

Werner continues:

‘I proposed many years ago for the Bank of Japan to create and pay out the equivalent of USD200,000 for each newly born baby – which would not cost the tax payer anything.

‘Such true ‘people QE’ would be the most productive use of credit creation, since technology drives the growth potential of an economy, and that can only be produced by people.

‘Moreover, each human born thanks to this policy would pay back this ‘people QE’ amount several times over through their lifetime contributions in labour, taxes, welfare contributions and other positive input into society.’

Demographic problems take decades to turn around. New babies aren’t productive until they reach adulthood, obviously. We may see the negative consequences of our ageing global population long before any solution today kicks in.

That doesn’t mean long-term planners can afford to ignore these issues. Not only could it help China secure growth, who know, it might be worth increasing the baby bonus down under, too.

Your friend,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.