Introduction

We warmly welcome Milo Brown, who’s joining our Wealth Morning writing team as an analyst.

He holds a conjoint degree in Commerce and Arts from the University of Auckland, majoring in Economics, Psychology, and Philosophy. His experience in financial services includes work as an AML and Verification Analyst, specialising in risk assessment and compliance.

He’s set to join the New Zealand Treasury as a graduate analyst, contributing to economic strategy and public policy. With a sharp analytical mindset and a multidisciplinary lens, Milo applies behavioural finance and commercial insight to investing.

We hope you enjoy his investigation into the potential of nuclear energy. No doubt, this is a controversial subject, but it might just appeal to contrarian investors with a rebellious streak.

The first time I heard the word ‘Chernobyl’, I was 13 years old, watching a TV drama where a man coughed blood into a sink. The camera panned to the swollen red rash across his back. The music got quieter, more sombre, and the drama of the scene was intense.

I wasn’t alive when the reactor exploded. I didn’t watch the Soviet officials deny the radiation. I didn’t smell the air or see the graphite fires light up the sky. I didn’t read or watch countless news articles on the event.

And while of course I sympathise with those who were there seeing and hearing nuclear tragedies unfold, for me, the horror of Chernobyl has become one more tile in a mosaic of 20th century tragedies.

I collected it in my mental archive of how I understood world history, but the event seems distant, disconnected, sometimes even academic. After all, there seem to be so many more horrific events in world history. So the ones I haven’t viscerally experienced are never at the forefront of my mind.

My mind, like others in my generation, prioritise fears that we have lived through. I remember being locked in a 4x2m dorm room for three months during the Covid pandemic, not able to speak to anyone, feeling distant and alone.

I remember being at a football tournament sitting under the marquee when the boy next to me found the livestream of the 2019 mosque shooting.

I have spent my entire life being taught to fear climate change.

Fires.

Drought.

Floods.

Every summer hotter than the last.

A planet tipping.

These events are the ones etched into my memory, making my heart race, my blood boil. But that’s the thing about memory: it’s not rational. It’s visceral. And I suspect my peers to feel the same.

You see, we didn’t live through the mushroom clouds or fallout shelters. We lived through the flooded homes and fire-blackened skies.

So now, in lecture halls, we talk about France as a model for zero-emission stability. In group chats, we debate the ethics. No one whispers the word anymore. We say it plainly: if nuclear energy is clean, safe, and constant, then why are we still afraid?

So it makes sense, in a strange way, that I’ve never recoiled at the word ‘nuclear.’ It doesn’t scare me. It fascinates me. I see it not as the threat of the past, but maybe, just maybe, the answer we’ve been ignoring for too long.

What’s unfolding isn’t just a change in technology. It’s a change in memory.

The kind that decides policy. The kind that decides markets. One fear is fading. Another is taking its place.

Eventually, the searing pain of memories that one generation feels begins to dissipate as the knowledge is passed on. Not because the next generation cares any less, but because they did not live through the moments that forged that pain.

The new generation inherits the facts, not the feelings. The fear, anger, and emotional weight attached to an event are gradually diluted as lived experience becomes second-hand memory.

What once felt like an open wound becomes, over time, a footnote in a history book. And what was once a visceral reality becomes a data point. A tragic but distant entry in the newer generation’s mental archive of the world.

For many older citizens, their relationship to nuclear is not based on theory or ideology. It is memory.

It recalls an era when the gravest threat facing humanity wasn’t climate collapse, but radioactive fallout. When schoolchildren rehearsed duck-and-cover drills. When the 6pm news delivered stories that made the air itself feel dangerous. A time in which the world sometimes felt on the brink of complete annihilation.

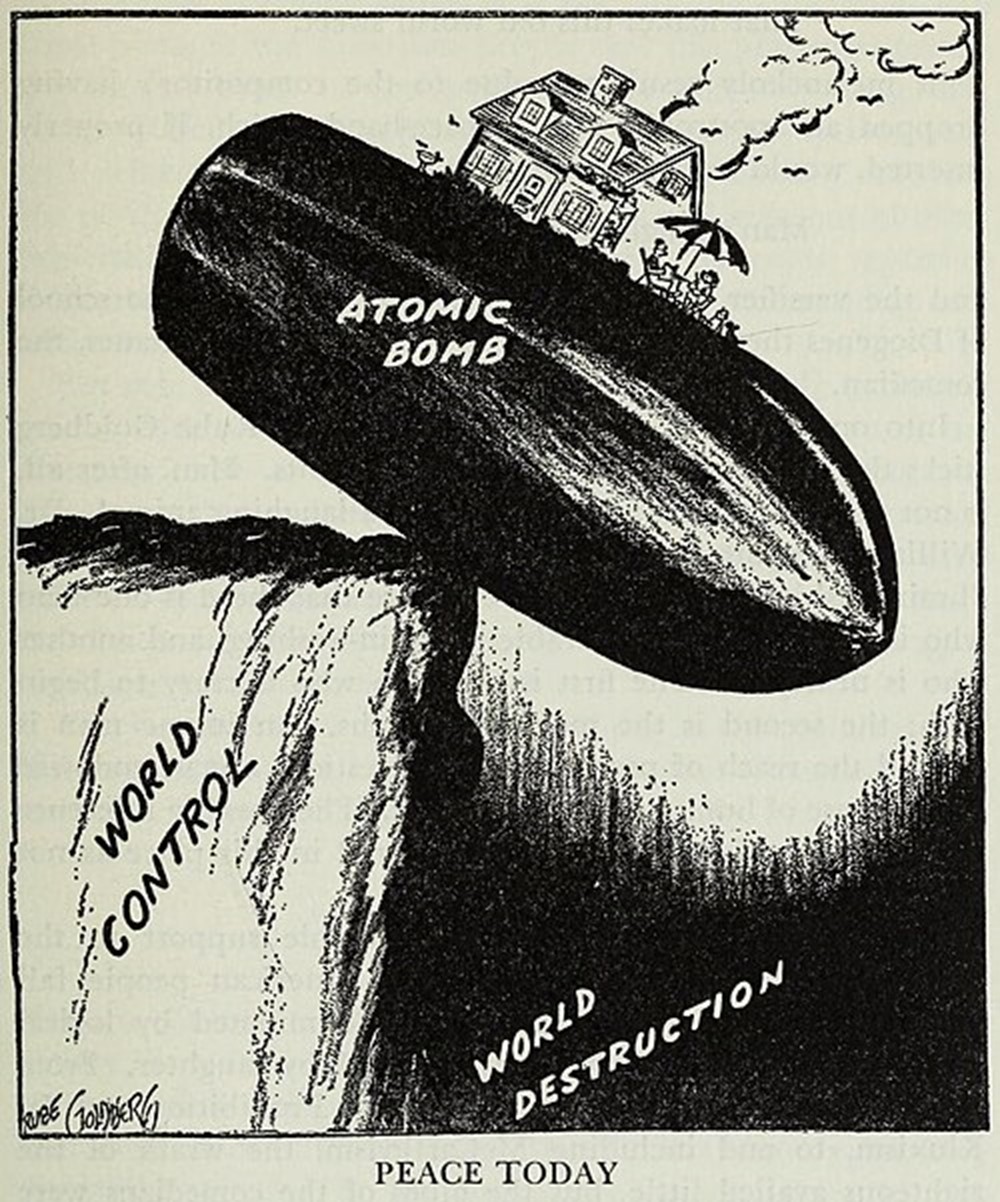

‘Peace Today’, the iconic Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoon by Rube Goldberg (July 22, 1947).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It’s easy to see how one might develop a deep-seated aversion. Hiroshima. Nagasaki. The Cold War arms race. Atomic test explosions filmed in black and white. Radiation leaks from facilities with names now seared into the global psyche.

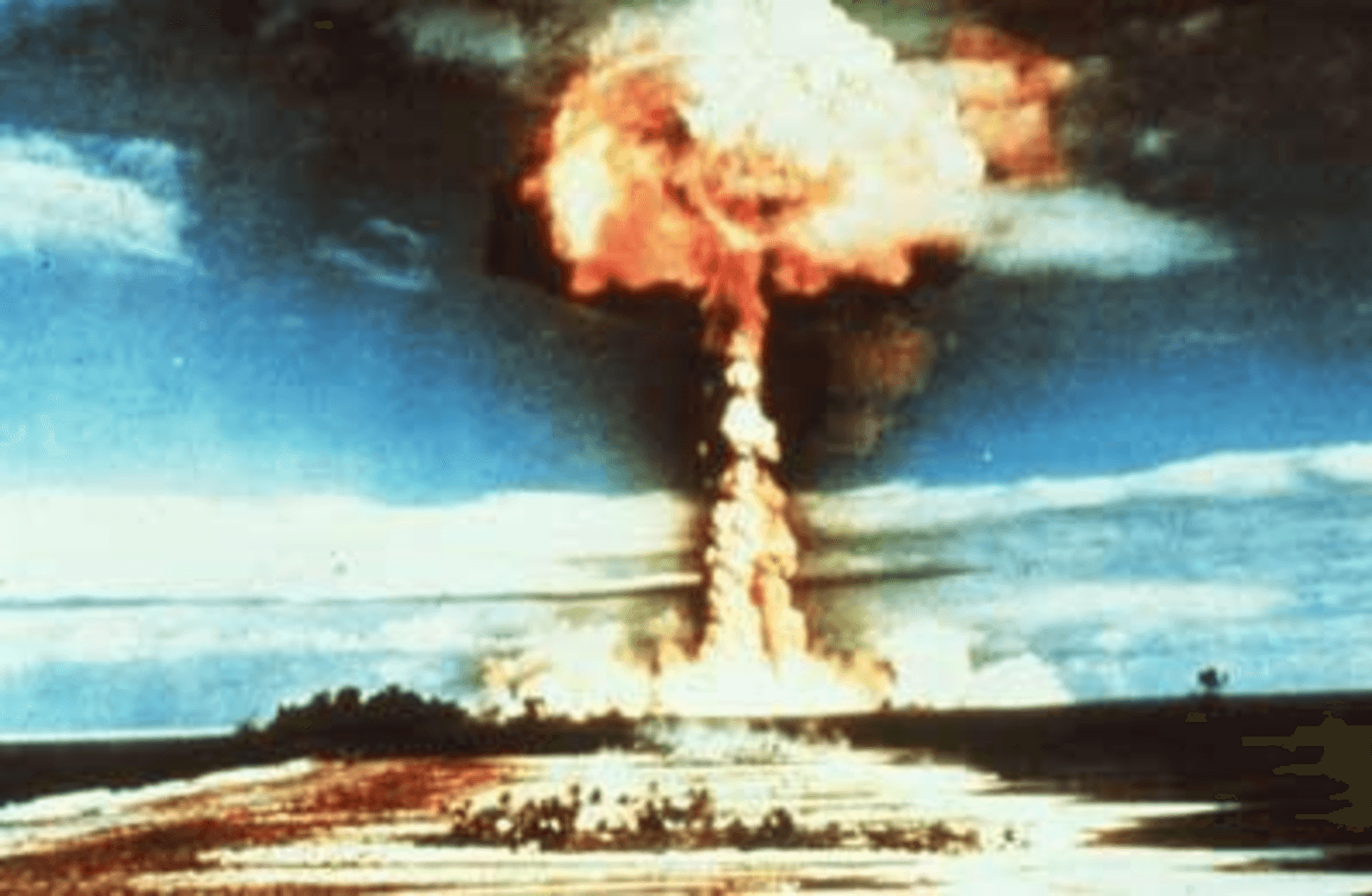

During the mid to late 20th century, nuclear tests in the Pacific became disturbingly routine. While most went as planned, a few did not. Accidents did occur, and when they did, the consequences were serious enough to dominate global headlines.

These moments weren’t hypothetical risks; they were proof of just how high the stakes were. The fear was not irrational. It was grounded in lived experience. The caution, well-earned.

In New Zealand, those emotions are carved into our collective identity. We remember Mururoa Atoll. We remember the French nuclear testing program and the radioactive drift it brought to our region. We remember the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour, a violent act on our own soil, tied to nuclear protest. Our anti-nuclear stance wasn’t just a foreign policy choice. It was a cultural declaration. A moral high ground.

French nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll, 1970. Source: New Zealand History

In 1987, we enshrined that stance into law, becoming the first Western-allied country to formally legislate a nuclear-free zone. It wasn’t just a policy, it was a defining act of national character. A proud line in the sand.

But lines drawn in one era often blur in the next. And as time passes, so too does the immediacy of the memories that shaped them.

The fear and scars are fading not because nuclear got safer (though it did), or because the disasters weren’t real (they absolutely were), but because a new, more immediate fear has taken its place, pushed by the mainstream.

Rising sea levels. 50-degree summers. Never-ending extreme weather events.

Australia’s Black Summer fires. The 2021 Canadian heat dome. The annual hurricanes swallowing US coastlines. The growing uninhabitability of regions in South Asia and Africa. Whether humans are driving these events or not is irrelevant, as what is undeniable is that the climate change messaging has been effective. Share prices reflect beliefs and attitudes, regardless of reality.

Today, a new generation who have absorbed all this messaging will be stepping forward and making decisions. A generation not defined by Cold War anxiety, but instead by climate paranoia.

Their fears are different and far less about radiation. After all, we weren’t shaped by the same nuclear legacy you might have been, and therefore it may be remembered differently by us.

The new generations see nuclear not as a danger to be avoided, but as a tool to be reconsidered.

So, if a whole generation is being taught to embrace the nuclear potential, or at least be open to it, might it be the case that when this generation becomes the decision-makers, old ways of thinking will be overturned?

The point is that whatever is being filtered through the minds of the youth today will become policy or action in the future.

Importantly, policy and actions are intrinsically linked to investment outcomes, making it crucial we understand the youth of today to protect our wealth into the future.

This change in attitude isn’t a rejection of the past. It’s an evolution of priorities. And in the face of escalating energy demand, fear-mongering over greenhouse gases, and geopolitical fragility, it may just be the kind of thinking the moment demands.

And here’s the irony. The very generation asked to think green, live sustainably, and ‘save the planet’ is beginning to ask questions:

- Why does wind power still rely on gas backup plants?

- Why can’t solar power a city through the night without billion-dollar battery banks?

- Why do countries that refuse nuclear end up importing coal?

The educational framing has changed. Wind, solar, and hydro might not be the supposed superheroes we need.

And that psychological pivot, from radioactive dread to climate anxiety, is quietly creating space to re-evaluate nuclear energy. The need to investigate the sector’s potential is getting more dramatic…

Your first Quantum Wealth Report is waiting for you:

⚡🌎 Start Your Subscription: NZ$37.00 / monthly

⚡🌎 Start Your Subscription: US$24.00 / monthly

Milo is an analyst and writer at Wealth Morning. He holds a conjoint degree in Commerce and Arts from the University of Auckland, majoring in Economics, Psychology, and Philosophy. His experience in financial services includes work as an AML and Verification Analyst, specialising in risk assessment and compliance. He’s set to join the New Zealand Treasury as a graduate analyst, contributing to economic strategy and public policy. With a sharp analytical mindset and a multidisciplinary lens, Milo applies behavioural finance and commercial insight to investing.