There are investments that make money. And there are ones that change the world.

An investment the American government made just after the Pearl Harbour attack was one of the latter.

Just after Pearl Harbour, the US government was offering up war bonds.

Some 84 million Americans forked out US$185 billion to buy these bonds (proceeds that went to the war effort).

The return on these bonds was paltry. Over a 10-year period, investors expected to make 2.9% on their money.

That’s why I say it was an investment by the American government, not the populace.

Like a venture capitalist firm, the government raise capital from the public, and then invest it to achieve the greatest possible return: Victory!

Not only did the US$185 billion sum help topple the Axis Powers. The government pulled American workers off the farms and trained them in factories. It was, in part, funded by these war bonds.

As a result, the government set the country up for a huge post-war boom.

Without raising taxes, the government was able to collect more tax revenue simply because corporate profits, household incomes and living standards were higher.

Ads for these war bonds called them ‘The Greatest Investment on Earth!’

And they were, for the government.

But it also kicked off a never-ending thirst for debt…

Debt is bad, sort of…

Individually, debt is a scary thing.

Especially since most of us in debt are paying interest on top of interest.

It’s not the kind of compounding anyone wants.

For the government though, debt seems pretty OK.

Or at least, that’s how some think.

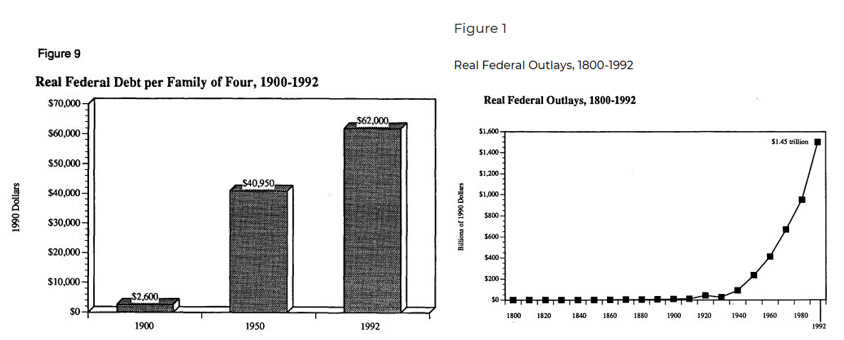

After the Second World War, the US got really credit hungry (left). And it’s because the government found a bunch of new ways to spend more money (right)…

|

Source: Foundation for Economic Education |

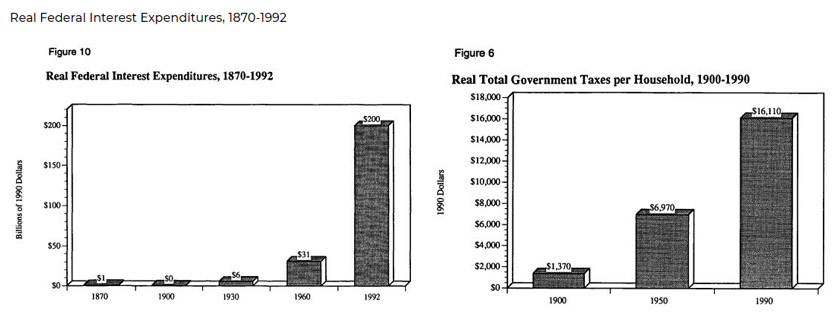

Because government debt expanded rapidly, so too did spending on interest to service this debt (left). Spending became so rampant, not only did the government need more debt, the tax burden on US households expanded many times over (right).

|

Source: Foundation for Economic Education |

People today continue to complain about this national debt accumulation.

The vast majority, however, go about their daily lives not even bothering to notice until election time.

Let’s leave the trillion-dollar figures aside as they tend to be used purely for shock value. The question is really about whether debt is bad or not.

So, is it bad?

If you said no, then give the credit card to your wife or husband.

Of course debt is bad!

This is money you owe to someone else. What’s more you need to pay interest, and then interest on top of interest for consuming this money.

This is how average Kiwis get into a hole.

They spend far more than they earn. They let debt accumulate. By that point it becomes extremely hard to pay off double or maybe triple what you originally owed.

So, if debt is bad for people like you and me, why wouldn’t it also be bad for governments?

Well, head of the US Federal Reserve (the US’ central bank), Jerome Powell seems to think so.

‘The idea that deficits don’t matter for countries that can borrow in their own currencies I think is just wrong,’ Powell said in front of congress. ‘We’re going to have either spend less or raise more revenue.’

Many tend to agree with Powell too. Here’s a Forbes contributor talking about a coming global reset…

‘At some point global government debt grows so large that merely rolling it over becomes a problem. The government will hit a debt wall and probably drag private debt down, too.

‘That will lead to what I think of as a worldwide debt default I call The Great Reset.

‘It is very difficult to predict the path The Great Reset will take.

‘We can’t know what the political environment will be as technology begins to eat into the employment rate.

‘Will increasing productivity reduce consumer prices or will inflation rise? If it’s the latter, will the Fed react by raising rates and trigger a Volcker-style recession? Will Congress order the Fed to monetize the debt?’

But the Oracle of Omaha thinks differently.

The Oracle isn’t worried

In his 2018 letter to shareholders, Warren Buffett wrote:

‘Let’s put numbers to that claim: If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter).

‘That is a gain of 5,288 for 1.

‘…Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods.

‘That’s 40,000%!

‘Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75.

‘And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.’

Why would one of the brightest investment minds not think huge federal debt is a problem?

Well, as long as you accumulate debt in your own currency, you can simply print yourself out of it. By that I mean, the government sells debt to the Fed or they get the Fed to buy their debt.

The Fed has the power to do this, for free!

They can simply print money, buy up a load of debt from the government, chuck in some private sector debt too if you want. And they can just sit on this.

This was something Japan did right after the Second World War.

The central bank bought up worthless war bonds from the government. They also took on some private sector debt from banks and other institutions.

The net effect was a healthy Japan and a healthy banking system ready to lend money.

Of course, too much of anything can lead to bad outcomes.

Japan over did it with their lending. Asset prices rose. The country saw one of the biggest bubble bursts in the 1990s.

Then there are the psychological implications to think about.

Such practices (getting central banks to buy up bad debt with newly created money) creates a terrible incentive.

Just imagine if US politicians knew the Fed would bail them out every so often.

Surely their spending would increase. Maybe tenfold.

What’s the point of balancing the budget when they can issue more loans to the Fed and spend in pockets of the economy to win over votes?

While the US might never go bankrupt, no care at all towards the federal budget could create a disaster of its own.

Your cautious friend,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.