What is the American Dream?

Where did it come from?

How did it make its mark on our cultural landscape?

In his book Origins of the American Revolution, historian John Chester Miller explored the mythic power of the frontier spirit. It shaped the culture of early immigrants in profound ways:

- Once immigrants to America had settled in their current home and attained happiness, they found this emotion to be fleeting.

- Soon enough, they grew restless. And driven by a thirst for adventure and risk, they would be tempted to move on, especially if they had heard of a better location further west.

- They were fixated on the belief that distant lands looming just beyond the horizon must be better and more prosperous than the ones already settled upon.

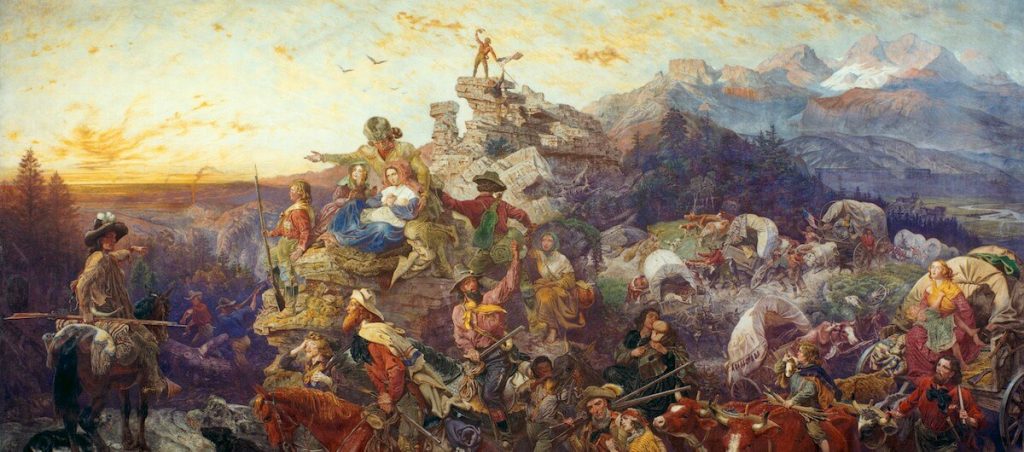

- Their boundless optimism gave rise to the period known as the Westward Expansion. It also cemented their faith in Manifest Destiny.

The romantic idealism of the Westward Expansion. Source: History

What is Manifest Destiny?

- It’s the idea that Americans were a special people, a chosen people. They had been blessed with the opportunity to settle upon a bountiful continent. It was their divine mission to expand, multiply, and prosper — from coast to coast, sea to shining sea.

- What exactly did that mean, in practice? Well, to put it simply, immigrants were no longer limited by the oppressive feudalism of the Old World.

- Children born into poverty and servitude were no longer doomed to follow in the footsteps of their parents. They could strive to be something more. Something better. If they dared to dream it, they could achieve it.

- This was the undeniable attraction. America would be a grand experiment in social mobility, never before attempted in the history of humanity.

The long hard road of becoming American

Of course, the romance of the Westward Expansion often clashed with the brutal reality:

- People of African descent endured the chains of slavery. People of Irish, Jewish, Slavic, Latino, and Asian background experienced discrimination. Native Americans arguably received the worst treatment of all — suffering murder and displacement from their ancestral lands.

- The second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence did proclaim, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

- Yes, this is true. But it was a principle that America struggled to live up to, especially in those early tumultuous decades.

- This gap between the haves and have-nots, the powerful and powerless, appeared difficult to reconcile.

Source: Vox

However, over time, something miraculous did happen. A powerful shift. That noble American experiment — that metaphorical tree of liberty — started to bear fruit:

- As historian Simon Schama pointed out in his documentary series, The American Future: A History, even those immigrants who were originally bullied and excluded began to find their place in the cultural landscape.

- Through perseverance, through determination, these people managed to capture their slice of the American Dream. They prospered. They were courageous to overcome those painful periods of transition.

- Indeed, this is how the America we know began to take shape. Its national motto rings true. E pluribus unum. Out of many, one.

Reflecting upon this, Simon Schama asked a rhetorical question, ‘What is an American?’

- Knowing what we know now, the answer is clear.

- An American is not white, or black, or brown, or yellow.

- An American is more than just the colour of his skin or his migrant roots.

- An American is someone who pursues an ideal. Who has an entrepreneurial streak. Who is a risk-taker. Who dares to believe that the grass on the other side will always be greener.

- An American is optimistic because he must be. He has the full weight of his nation’s vibrant history behind him. He is Manifest Destiny personified.

The Chinese rice bowl

If Americans are defined by their forward-looking optimism, then the Chinese must surely be defined by their collective anxiety:

- I learned this pretty early on in life. I’m a fourth-generation Malaysian of Chinese Fuzhou descent. So my childhood was spent listening to traditional proverbs from my parents.

- ‘Are you able to fill your rice bowl?’

- ‘The rice bowl is the same the world over.’

- ‘Do not put sand in another person’s rice bowl.’

- Loose translation: there’s nothing more important than being fed.

- So, if you take on a career, make sure it’s enough to keep you fed. If you emigrate to another country, do it to be fed. And even if you don’t like another person, make sure you don’t disrupt their livelihood and starve them, because that’s bad.

This obsession with rice bowls — and being fed — might come across as strange. But when a history of hunger looms large in your subconscious, you can’t help but agonise about it:

- My great-grandparents fled China to escape war and famine. Their harrowing ordeal continues to resonate in my family. The raw stories that have been passed down still have the power to evoke both melancholy and terror.

- Hunger is a theme that haunts the imagination of the overseas Chinese who don’t live under communist control. These are the descendants of immigrants who settled generations ago in Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and elsewhere.

- Hunger is a theme that forms an authoritarian stranglehold for the mainland Chinese who do live under communist control. There’s a quote from Deng Xiaoping that goes like this: ‘To be rich is glorious.’ But, really, the true meaning is this: ‘To be rich means we’ll never have to starve again.’

This isn’t a uniquely Eastern melody, of course. You may find echoes of this in the Western world as well:

- A friend from Ireland once told me, ‘To be Irish is to remember.’ He was talking about the history of the Great Famine in his homeland. The one where potato crops failed, condemning almost a quarter of the population to die, forcing many survivors to emigrate.

Well, that’s the kind of existential trauma many Chinese can relate to:

- For 2,000 years, there were over 1,800 recorded famines in China. Historically, no province was left untouched. They suffered approximately one famine a year.

- For the mainland Chinese, in particular, this feeds into a narrative that promotes authoritarianism and ultranationalism.

The century of humiliation

Western powers perceived to be carving up China in the 19th century. Source: Wikipedia

One incendiary message that’s reinforced again and again is the so-called century of humiliation:

- This was the period in history when China suffered a series of defeats against foreign adversaries.

- In fact, the first economic conflict between East and West happened for reasons that have eerie parallels with what we’re seeing today.

It unfolded like this:

- In the late 18th century, the British Empire loved tea.

- China was the world’s biggest producer of tea.

- A trade deal was established: British silver in return for Chinese tea.

On the surface of it, this felt like a clean and simple deal. A willing buyer. A willing seller:

- Problem was, over time, the British Treasury ran low on silver, even as the Chinese government became comparatively wealthy by hoarding silver.

- This trade imbalance gave rise to bitter emotions. And in an attempt to replenish their coffers, the British decided to establish a new agreement.

It went like this:

- The opium drug would be imported into China.

- Silver would flow back to Britain.

- The trade deficit would be resolved.

Unfortunately, this plan soon hit a snag:

- The Chinese government became alarmed at the large numbers of its citizens becoming addicted to opium. And in the name of morality, they halted British shipments, seizing and destroying the drug.

- Enraged, the British sent warships to reopen Chinese ports.The Opium Wars erupted.

Source: Welt

China lost this conflict. Badly. It was not only forced to yield to British trade demands, but also surrender control of Hong Kong to the British:

- This was a painful chapter in history. It continues to resonate in the Chinese psyche, fuelling nationalist sentiment. It’s something that the Communist Party gains mileage from.

- They have come to believe there’s a score to be settled across centuries.

- Xenophobic? Yes. Effective? Absolutely. You only need a grain of truth to exploit people’s deepest fears about loss and deprivation.

The bottom line

Winston Churchill once said, ‘Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.’ But he could just as easily have been talking about China:

- Today’s headlines tend to portray the conflict between America and China in economic and military terms, with the motives of the Chinese Communist Party often shrouded in mystery. But, really, it’s the cultural context that’s the most important.

- America is a land of plenty, which is relatively resource-rich. For this reason, the mindset of its people is geared to grow with confidence.

- China is a land of scarcity, which is relatively resource-poor. For this reason, the mindset of its people is geared to expand with anxiety.

If you believe that geography is destiny, then it’s no surprise that America and China have come to blows. They have different outlooks. Different perceptions. It’s about American plenty versus Chinese scarcity:

- Still, even amidst the hostility and turbulence, we encounter a strange fact. The Chinese actually have a unique name for America — which, upon reflection, is quite unexpected and poignant.

- They call America ‘Meiguo’. Which, directly translated, means ‘Beautiful Country.’

- It’s a tacit acknowledgement that the American Dream, while not perfect, still has great inspirational power. After all, America was arguably the first country in the world to promote this grand experiment of social mobility, regardless of race or class.

The Chinese — though they may never admit it outright — crave this same ideal, but are trying to achieve it within an authoritarian communist framework:

- So, here’s the big question for this decade: will these political contradictions resolve themselves peacefully? Or will conflict beget conflict? A new Cold War? Only time will tell.

- Hopes and dreams; trauma and loss; yin and yang — that’s what’s driving these two proud cultures into a collision course, even if they don’t consciously know it.

It’s time to have your say

I hope that you’ve enjoyed reading our articles as much as we’ve enjoyed writing them:

- Your prosperity is our focus — which is why we are always working hard to uncover new opportunities beyond the radar for you.

By the way, I have a small favour to ask:

- Would you like to write a review of our work here at Wealth Morning?

- Do you want to let us know if our stories have inspired you in a positive way?

- Do you want to let us know if our stories have helped you become a more successful investor?

We truly value your feedback. It encourages us. It helps us to do better. It helps us to reach further:

- So, if you’d like to leave us a review, it’s quick and easy. It will only take two minutes of your time.

- Thank you so much in advance for your kindness and generosity. Your readership keeps us going!

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.